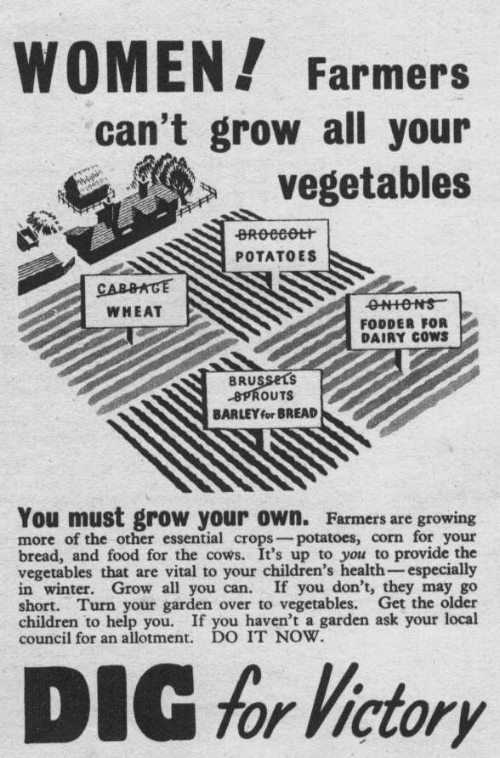

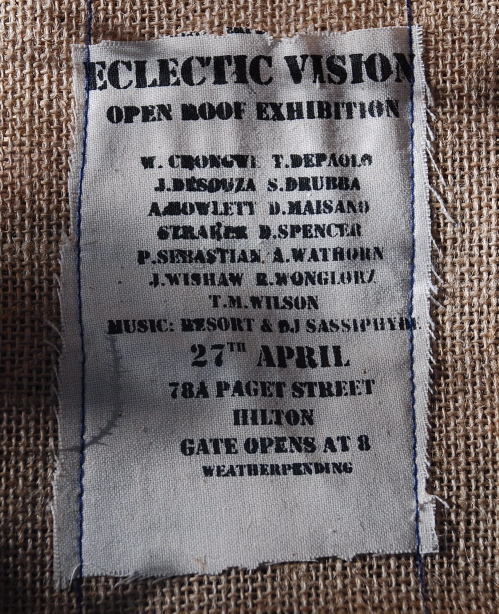

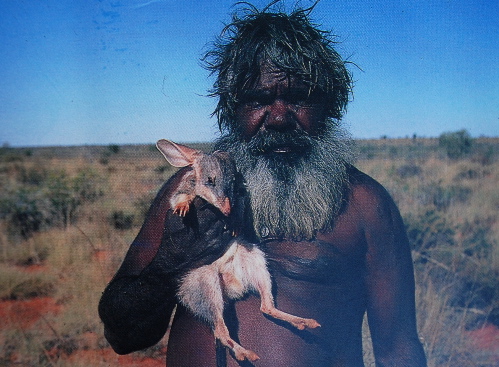

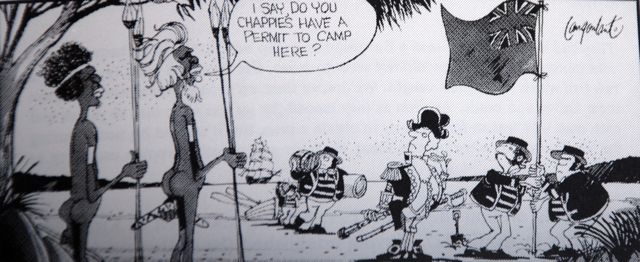

[Today I’m going to publish a bit of writing by Julia Denton-Barker (my mum). She has recently written a retrospective piece about a farm in Cornwall where she lived many years ago. Reading it doesn’t just make me sad for the loss of the traditional English farm and associated folkways, it also makes me reflect on the immense difference between producing food in England prior to the 1960s, and producing food in Australia today. The former seemed to allow a kind of humane intimacy between humans and the land, while the latter most often seems to lack such any such rapport. Anyway, time for me to stop writing.]

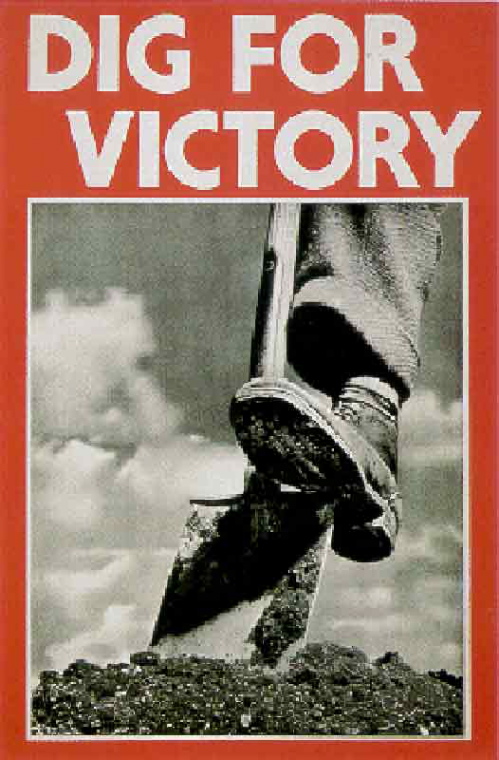

When they first bought the farm, they had to learn everything from the beginning. Despite lots of experience with a large (and organic) garden, a productive orchard, plenty of chickens, rabbits and the rampaging goats, they had no idea at all about the work involved in running a dairy farm. It was a large place by local standards, nearly 200 acres, although I may remember that wrongly and it could have been much smaller. In those days, milking 24 cows everyday, twice a day, was considered to be a useful contribution to the farming economy, whereas these days it wouldn’t be ‘viable’. They dived in, full of positive expectations.

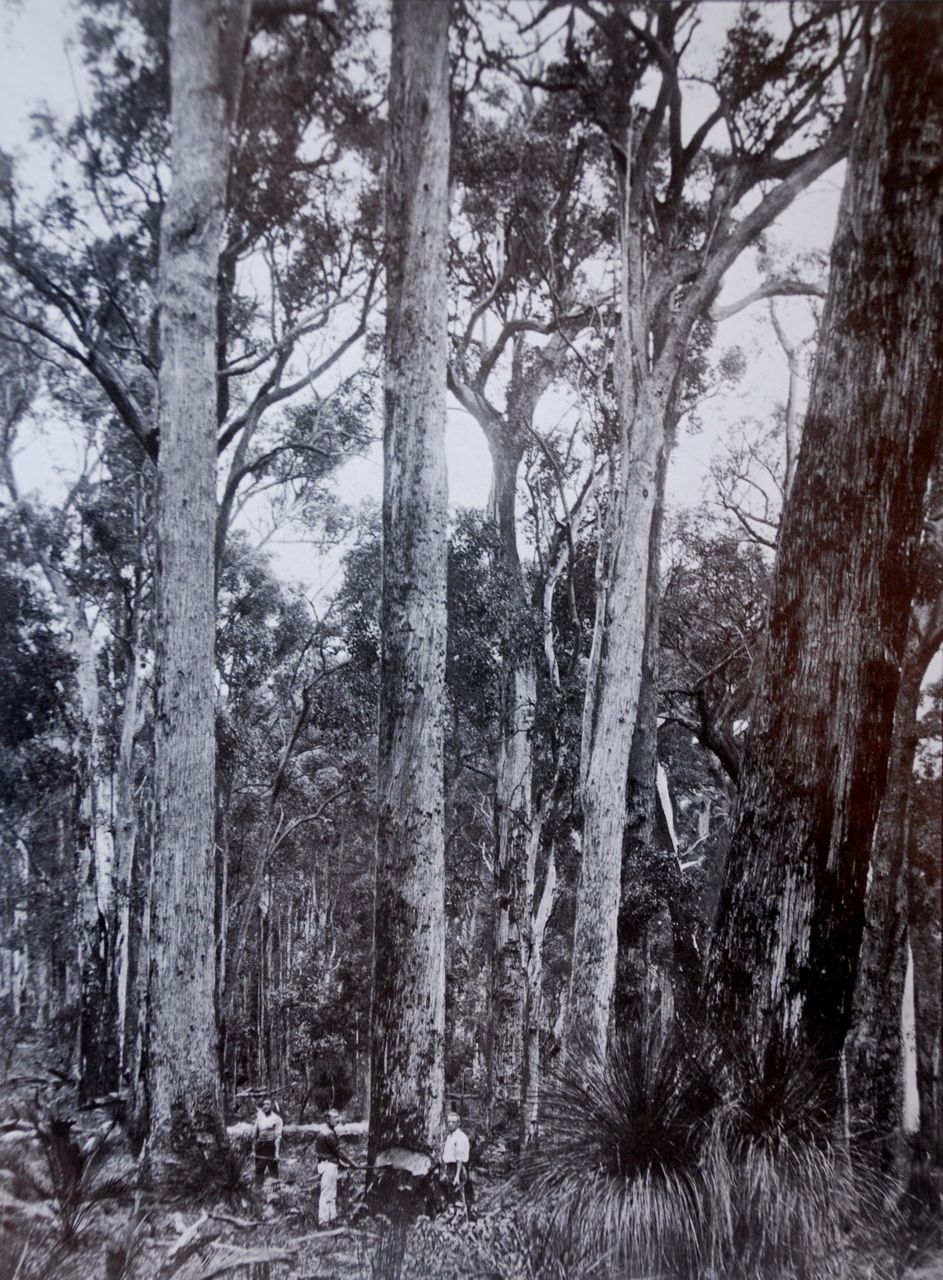

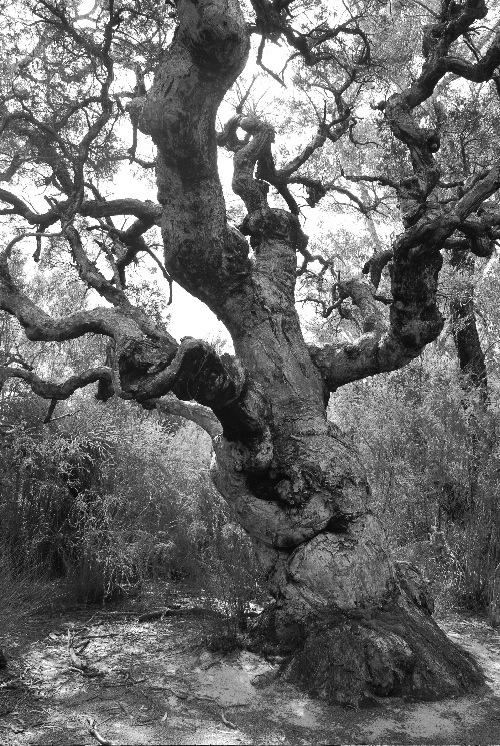

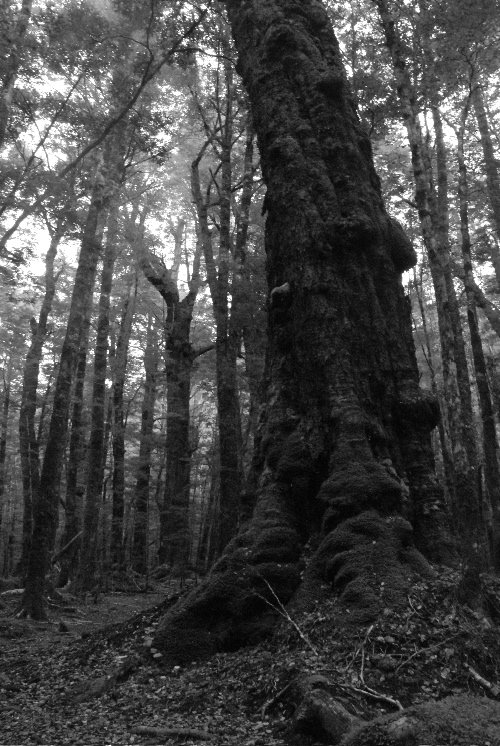

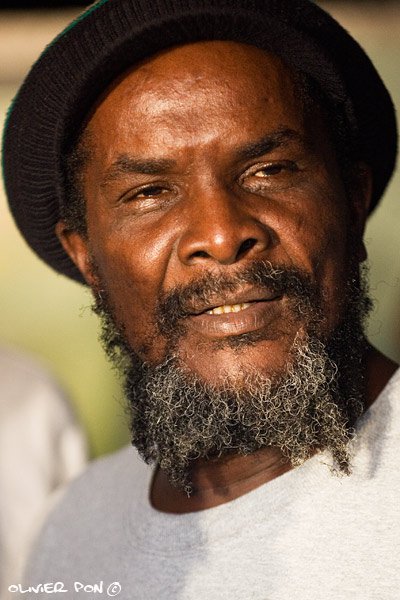

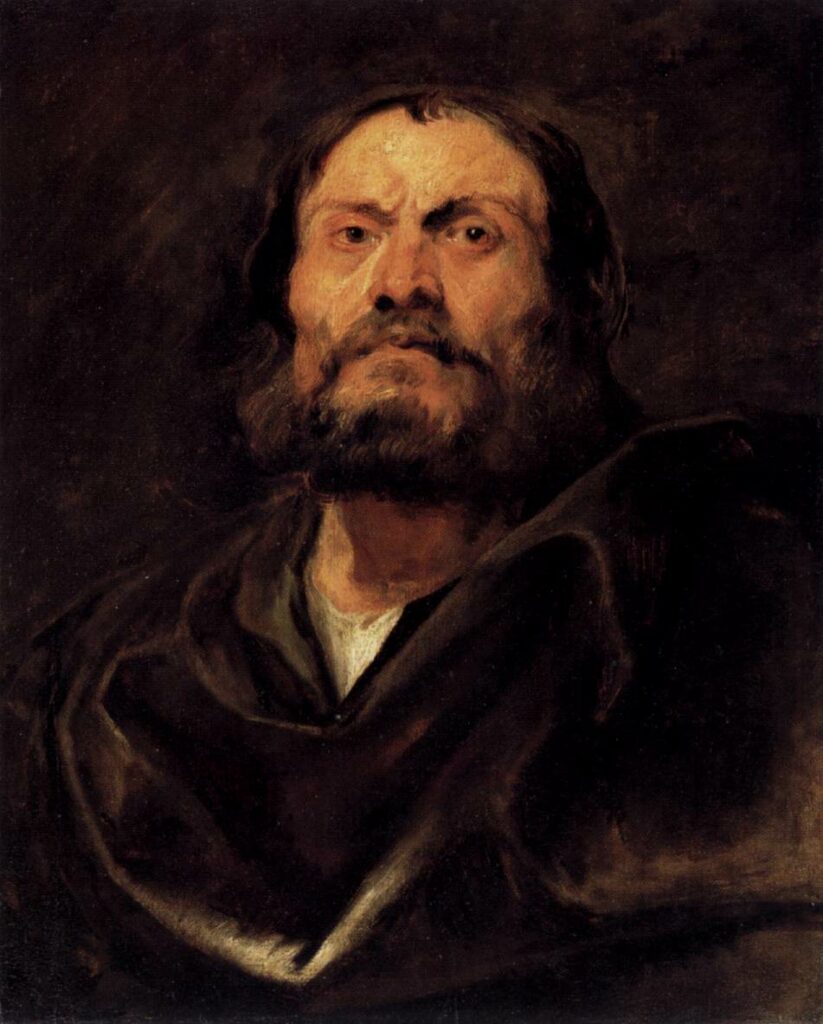

The farm had been owned by William Tregear, and possibly his sister, but by the time he had decided to sell it, she had died. He had lived there all his life, and had worked the farm with three or four Clydesdale horses. They were in the top home field, the first day that I went to the farm, and their huge heads hung over the gate as they watched the activity in the yard. It was the last farm in that part of Cornwall to have working horses, possibly the last farm in the south west of England, and Willum, as he was called, had no time for tractors. He was a large man, usually wearing an old dark tweed jacket with a hessian sack tied (with binder string) around his waist, sagging and stained trousers and boots that looked as though they were welded on to his feet. His nose was a beacon: it took up most of his face, florid and enormous, like a large red cauliflower, and the skin was veined and mottled, from his life of being outdoors in the gales and rain of West Penwith. We stood in the farmyard, that first day, and he slowly brought words up and out into the daylight. His entire life had been bounded by the farm and the area between Sennen and St. Buryan; somehow the subject of ‘elsewhere’ came up, perhaps because we had told him that we had lived in the Welsh Borders, and he paused, considered, and carefully told us, “Well, yesss, you know that, I did go to England once, you know, yesss….” and he stopped again for a moment. “I went to Plymouth, you know, well, in fact I did go a couple of times,” and he considered this, thinking about England again. I felt the weight and depth of what it must mean to be so strongly grounded in this place, and how the Cornish land was still held to be a different nation with its own identity. Willum Tregear was a Cornishman, and he wasn’t English.

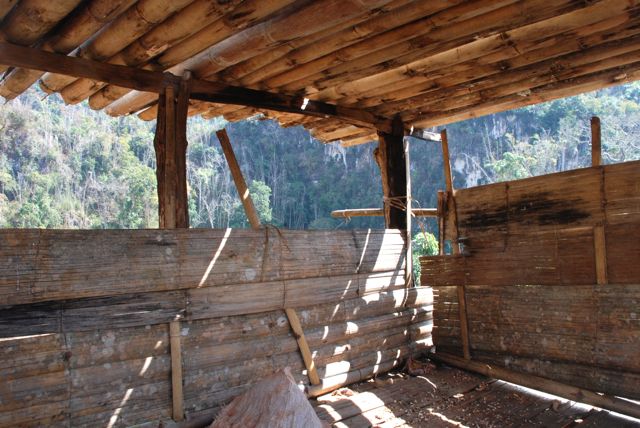

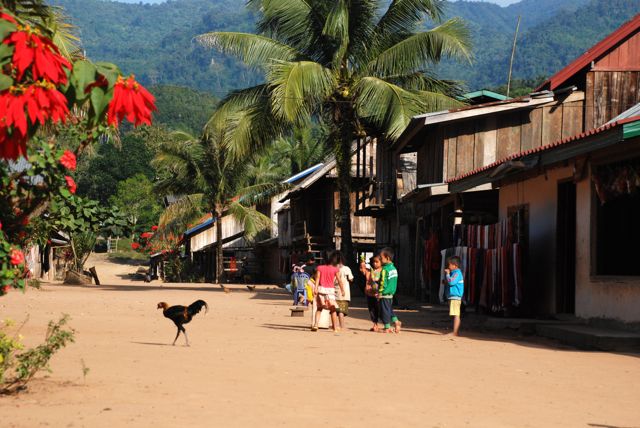

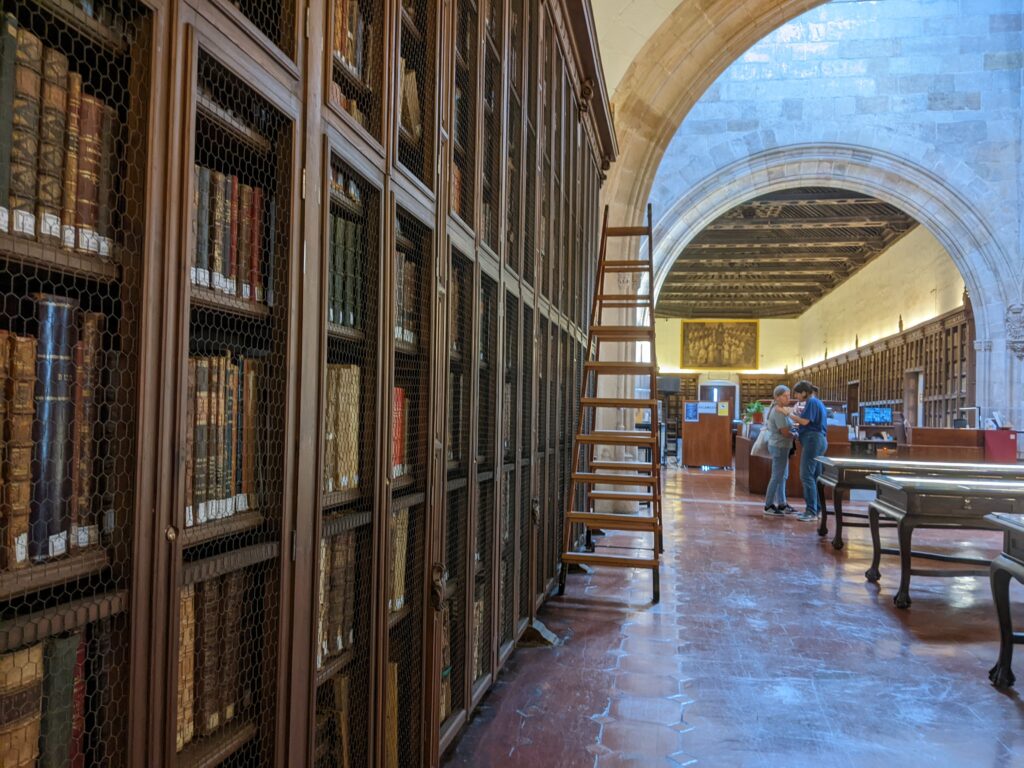

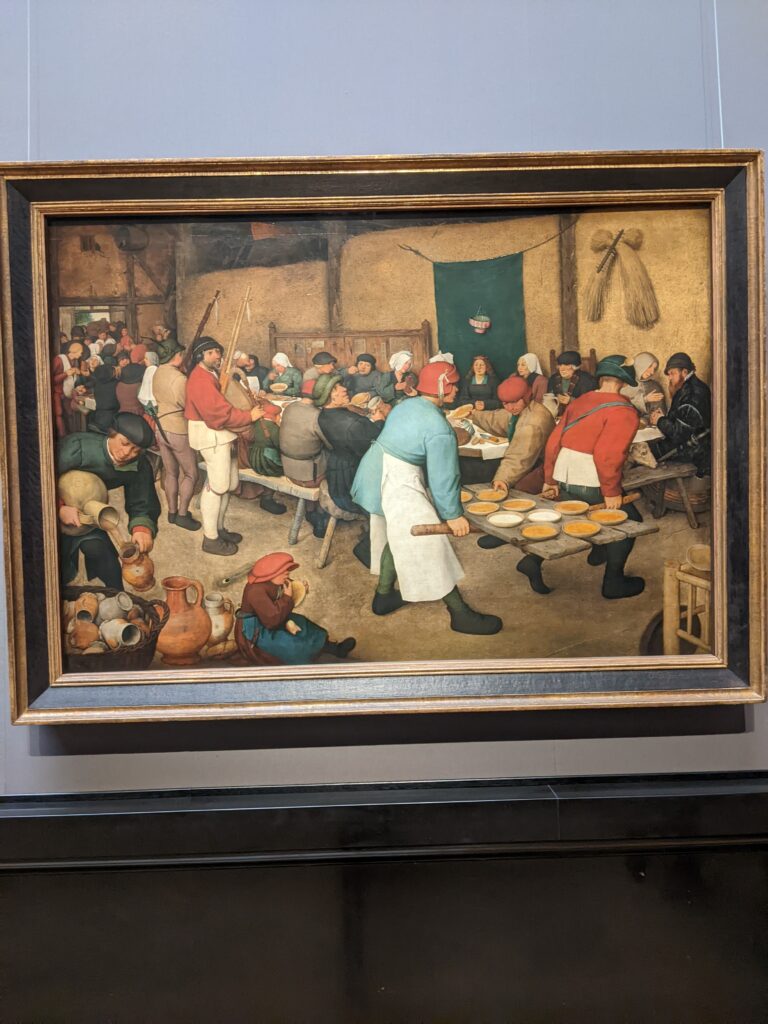

The farmyard where we stood that first afternoon, talking, looking around, waiting for whatever he may be able to tell us next about the farm, was ringed by low granite barns. At the top of the yard was the hay barn, two stories, with opened dormer style shutters and below were the horse stalls. An opening in the wooden upper floor meant that the hay could be easily thrown down to the horses; there were cobblestones on the floor and ancient stone troughs for their feed, and wood partitions were rubbed smooth from uncountable years of occupation. Next to the stables was the milking shed: long, low, and with a spotless concrete floor. Each cow had her own place, her own spot, and when the gate was opened for them at milking time, they ambled gently into the cowshed, straight into their places and keenly pushed their heads down to eat their allocated food. Willum had twenty four Jersey and Guernsey cows, each one known well and clearly loved deeply. We watched him milk, later that first afternoon, quietly going up and down the row of cows, working as he had done for over sixty years, and the cows stood, calmly chewing, while the milk was taken and pumped into churns. There is a particular smell to milking parlours, composed of cow manure, disinfectant, hay, cattle feed, and the soft warm taste of fresh milk too. The milking took place in silence, or at least without the noise of talking; there was a low hum from the milking machine, and the sounds of chewing cows, the swish of their tails, the clank of the buckets as Willum hefted them to carry the milk into the adjoining small barn to be measured and poured into larger churns. It was a peaceful and measured way of working.

Next to the milking shed was the longer barn which was used to house the new litters of pigs: empty that first day of animals. The pens were roomy and clean, covered in fresh straw with corner areas cordoned off, separate so that the piglets could sleep without being squashed by their large mothers. Then, at the end of this row of barns was an old, near derelict cottage, with broken windows, and no front door. Inside, the second floor had been almost completely taken out, so that the roof tiles were visible. One corner of the old floor still stood, held up by roughly placed timbers, and the whole building was filled with hay bales, stacked right to the roof in the back and coming down like a large staircase to the old front door. The smell was sweet and strong, and the only sound inside amongst the hay was of faint rustlings of the mice and of swallows coming and going to their nests, lining the rafters.

The house stood on the other side of the yard, which was roughly paved with stone, but muddy with the activity and use of a working farm. The two sheep dogs lay quietly watching every move that Willum made, waiting to work; the younger collie inched closer to his master, waiting hopefully. Chickens pecked around the dung heap that pushed up against the cowshed wall, and in the middle was the well, which had low granite blocks as a wall, no roof, and an ancient galvanized iron bucket resting on the stone, and some rope roughly tied around the handle. This was the house water supply: there was no running water and no bathroom in the house. A scullery served as the kitchen, a lean-to built as a much later addition to the rest of the farm, and this held two rickety wooded benches with large enameled, white bowls for the washing up and perhaps, too, the washing. The farm had probably not changed for fifty years or more, although there was now electricity. No telephone, though, and no need for such a device.

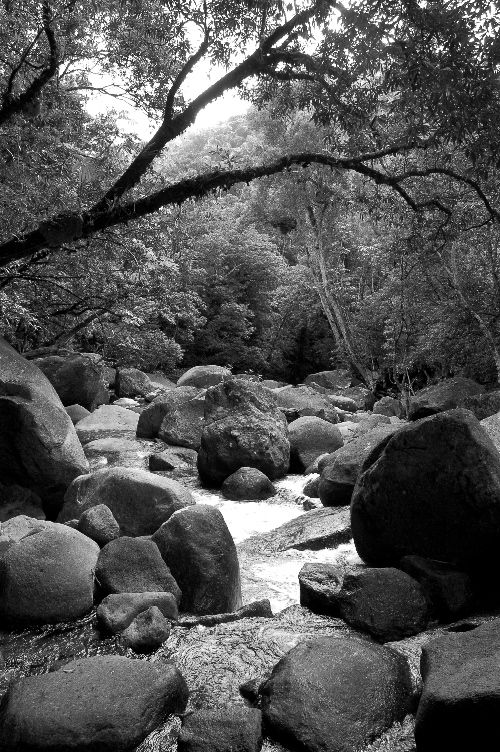

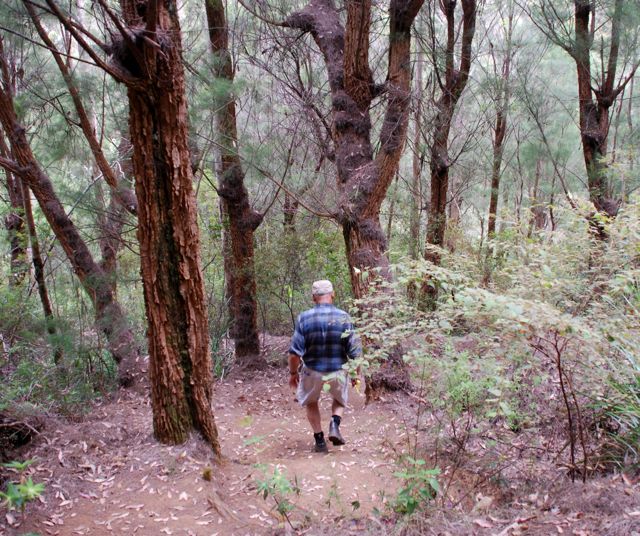

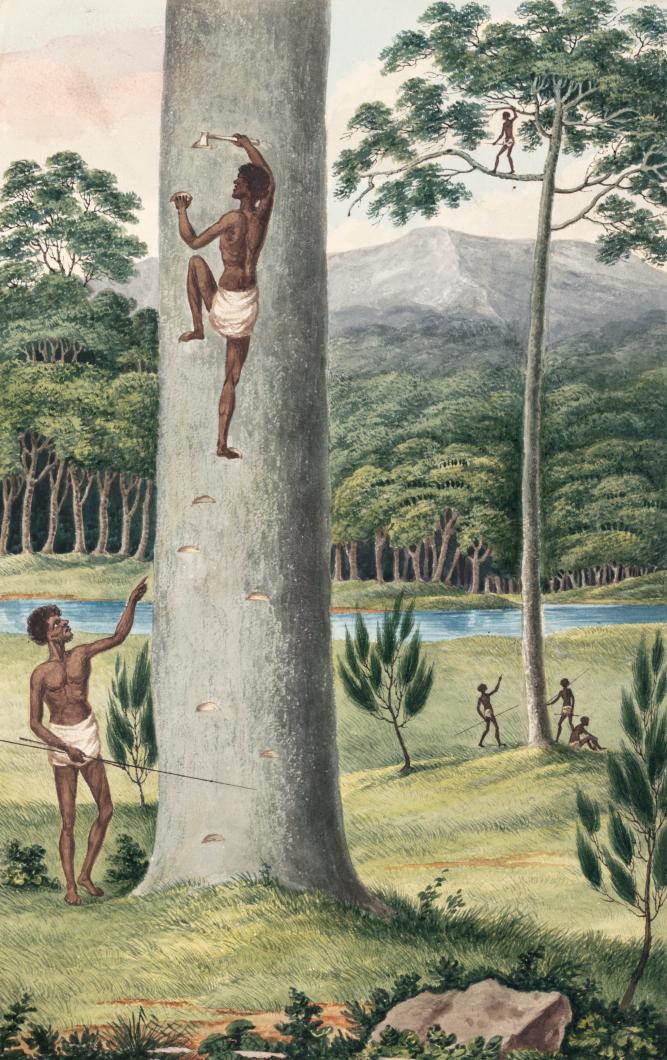

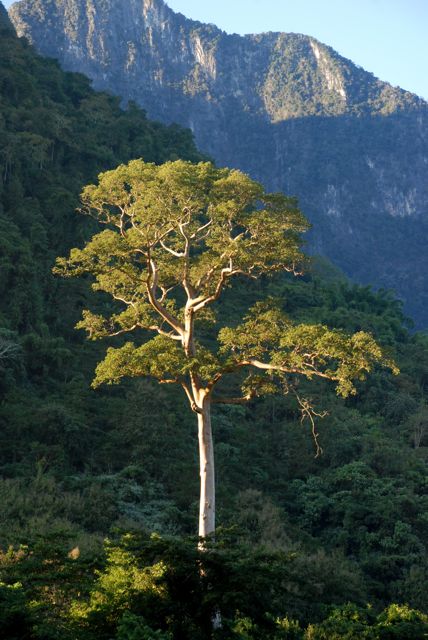

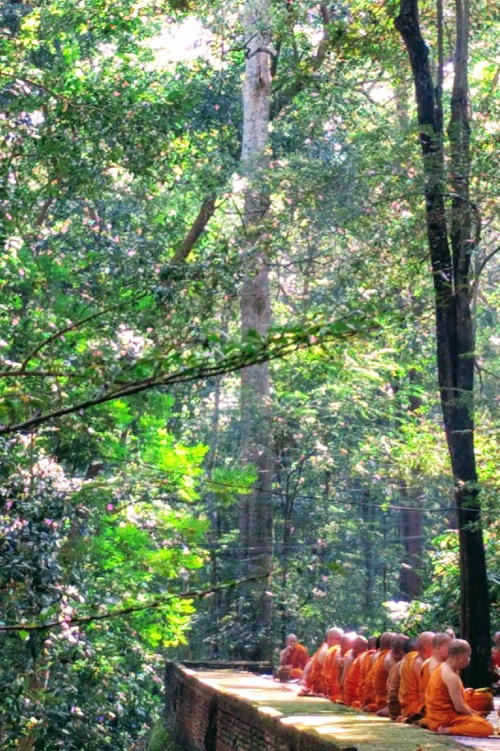

The land went up gently behind the farm buildings, towards the hill, Chapel Carn Brea, which stood to the east. Each field had its own name, and its own character. He led us round, up past the fields where the cows were pastured, through old wooden gates tied with string and bits of wire, up on to the higher ground. There was another old abandoned cottage up there, standing with its windows open to the weather, and holes in the walls where the granite rocks had fallen, lying in the bracken now, and in the cottage just mud and a rocky floor, where the cattle had sheltered from the weather. Up here were the beef cattle, perhaps a dozen at most of Aberdeen Angus, young creatures who came bunching up around us in curiosity and affection. Willum knew each one of these beasts, naming them and giving each one its history. Each field on the farm was contained, held, protected by stone walls – he called them hedges – about the height of a man, these walls were covered in flowers, gorse, moss and lichen, ancient granite blocks which stopped the wind and rain from eroding the land and which gave shelter to the birds and small creatures. The fields were small, each with its own special character, and the grass was patched with bracken and clumps of gorse bushes. As we walked, the only sounds we could hear was that of the larks, the cattle, and the wind; the air smelled sweet with the yellow gorse flowers and the damp familiar bracken. The dogs ranged around us, back and then away again.

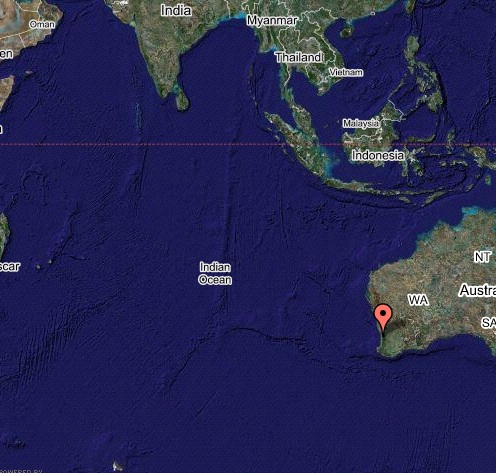

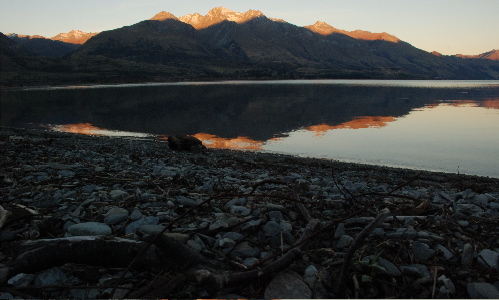

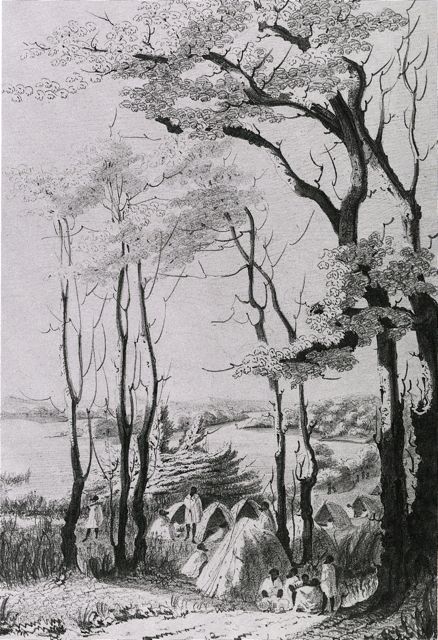

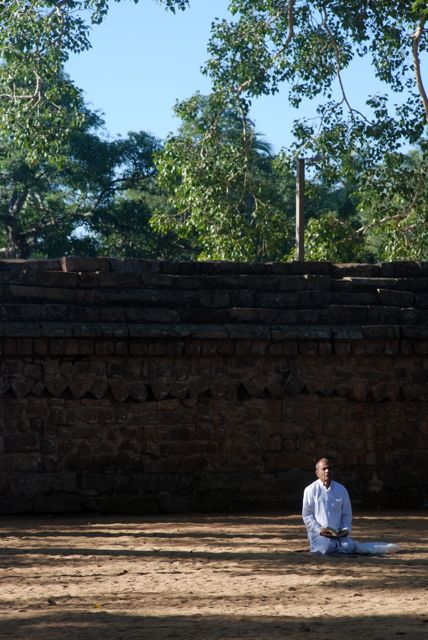

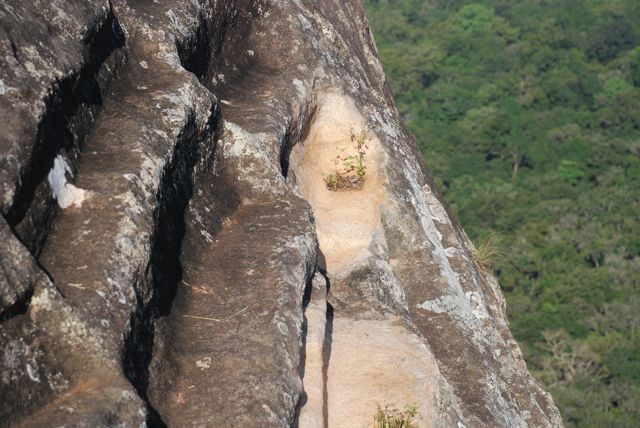

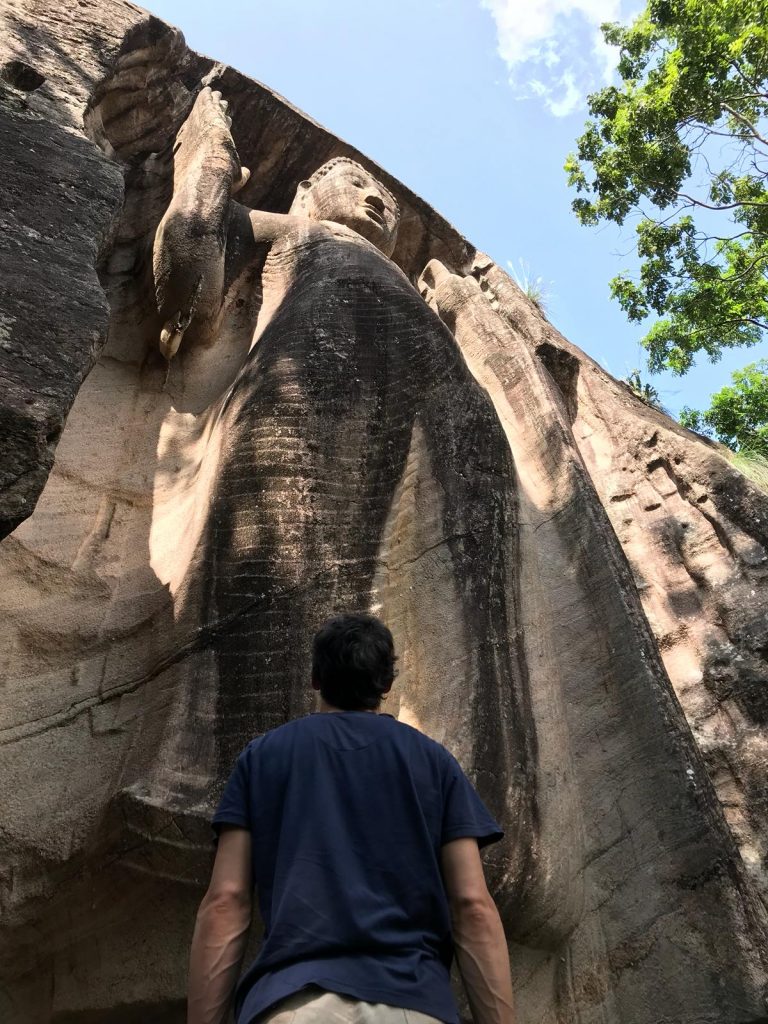

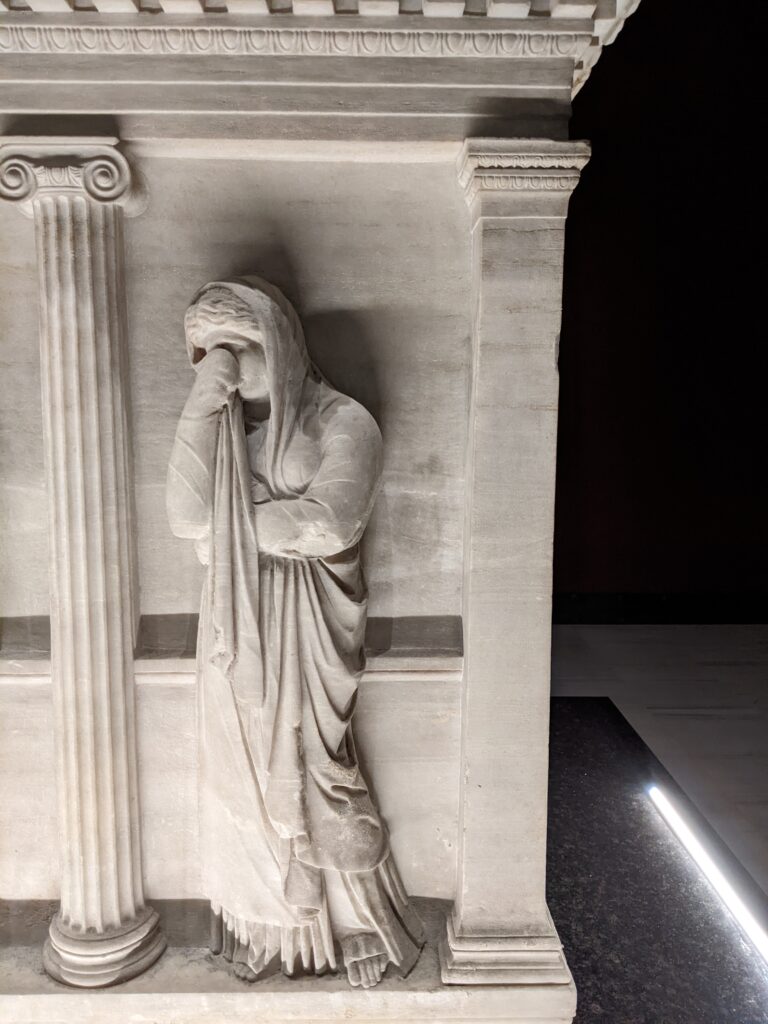

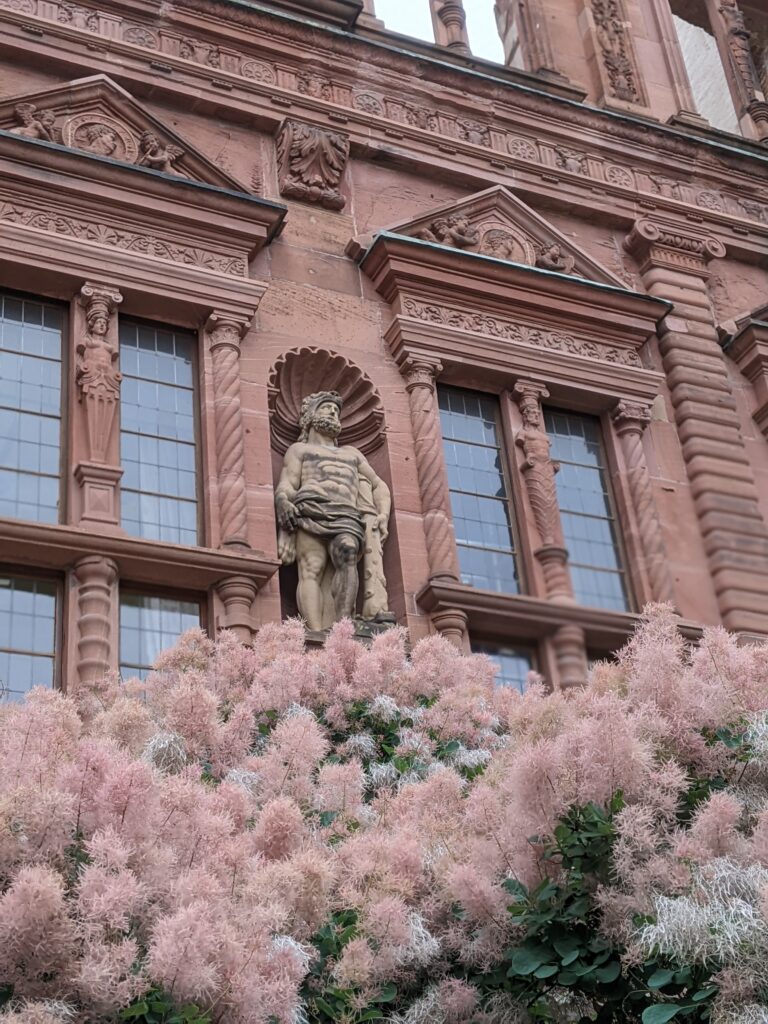

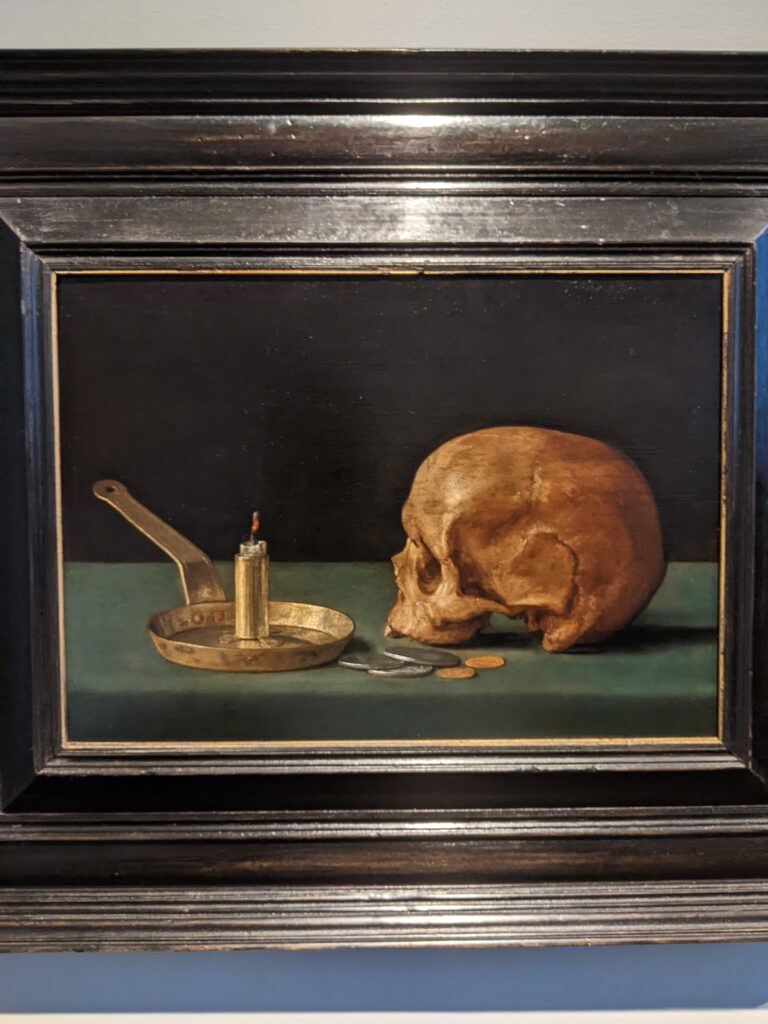

Higher up again, on the top of the hill, the view stretched right around the whole peninusula. The path up to the top was narrow, winding up through the gorse and low bushes, past tall blocks of granite: standing stones, some of them, ancient and placed there for ceremonies, perhaps and for reasons that we could never know. We looked out over Lands End, towards the islands, and back towards Penzance: a networked web of small fields, outlined by the hedges, dotted with cattle. There weren’t many trees, as the wind howls in from the Atlantic in West Penwith, but in the valleys there was the glimpse of shelter and a sense of mystery and hidden beauty. The wind was strong up there, and the rocks held their own power. The stones tumbled up into a large mound were, he said, the remains of the Chapel of St. Michael, built there in the earliest times of Christianity in Britain. Beyond this stood standing stones, grouped together, still erect, silent, with a curiously forbidding sense about them. The view was as wide as the world, and we stood, with no words necessary, looking out over the patterned, unchanged landscape and aware of the gift that had been granted. William Tregear was no longer able to work his farm, but if he handed it on to us, we could work to be stewards, truthful caretakers, and hold the long occupation of this land in trust. I fell in love that day, for the first time knowing that one particular place, this place, the air and the wind and the earth, could be a source of immense joy, comfort, peace. I was to spend many long hours on the hill, absorbing the spirit of place, loving it, dreaming, losing myself in delight.

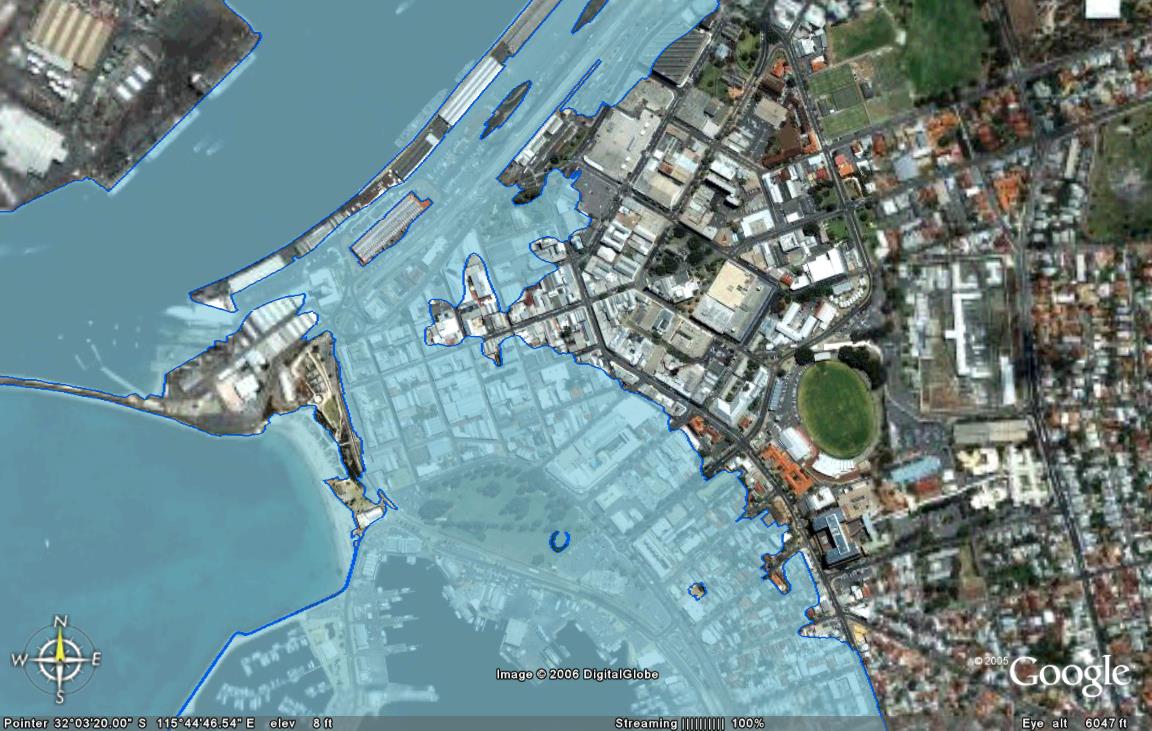

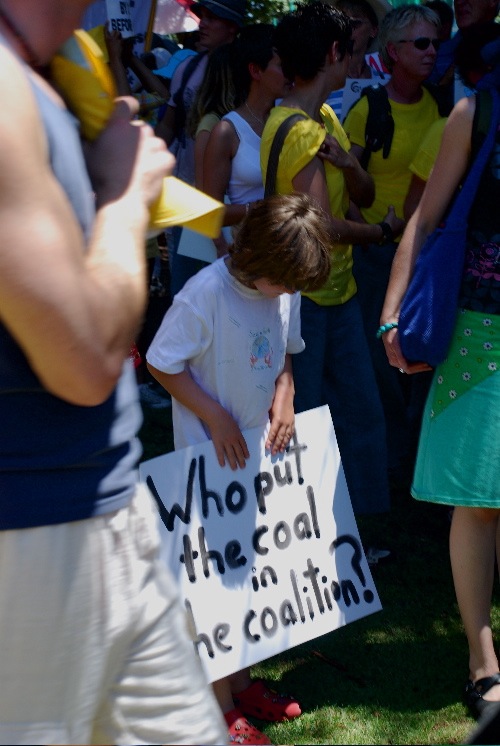

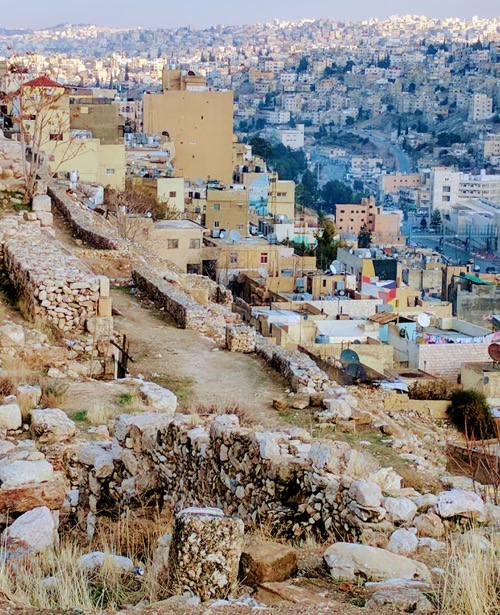

My parents only lived on Kerrow Farm for about seven years, before selling it and moving to the Balearics, and then, on to Australia. The history of each field, and the continuity of use, ended with them. They milked the same number of cows as Willum, and ran some cattle up on the top fields, and they kept pigs for a time, grew beets and kale for winter fodder, and brought the hay in, just as it has always been done. But when they sold the farm, the new owner knocked down all the old stone ‘hedges’, in order to make the land ‘profitable’ for larger scale farming. He planted one crop over the whole area, one crop on one large field where previously had been five or more small, enclosed and healthy fields. The wind blew the soil away, and destroyed the crop, and the rain washed earth down onto the bottom road, and away off the land. He sold the house, then, to a local business man, and the monoculture continued with cattle, first, and then more crops. The price of the land went up and up, so that only rich agribusiness farmers could afford to buy it when it went back on the market.

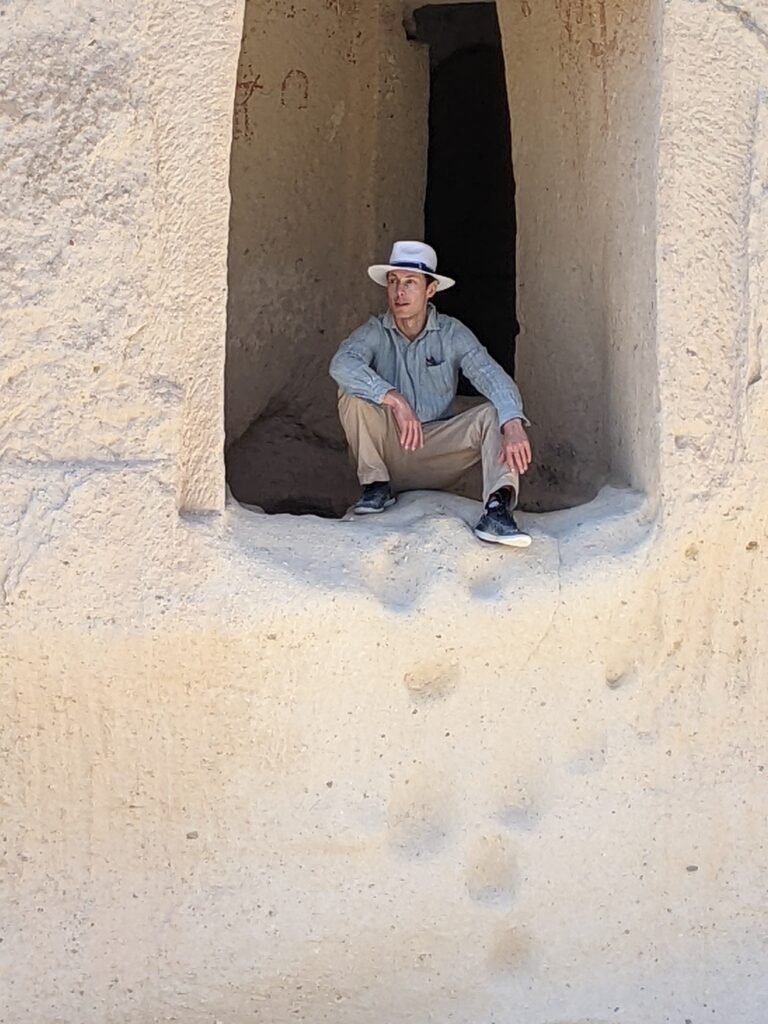

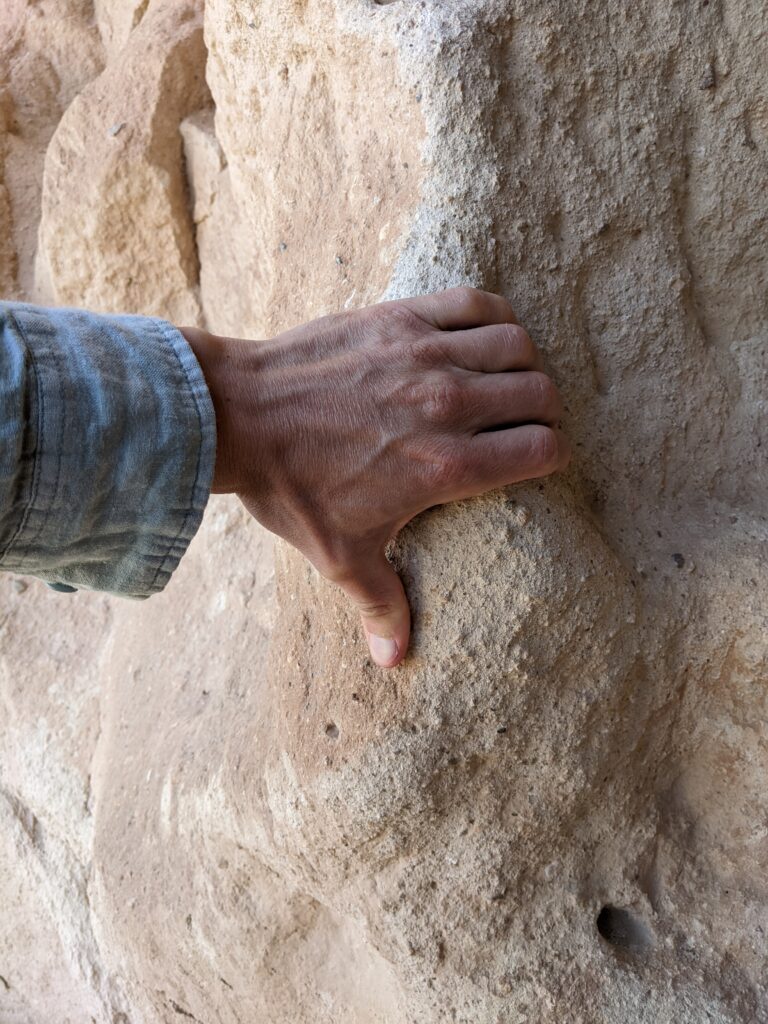

Last year I went back to Kerrow for the first time in nearly forty years. I went first to the top of the hill, and walked, and gazed, and heard the larks, and smelled the gorse, still sweet like special honey. I climbed onto the top of the rocks, looking out over the land towards the sea, and out to the Scilly Islands. The sky was luminous, blue, clear, and I rubbed my hand against the rough granite, closing my eyes, knowing suddenly that I was home again. The path still wound down past the stones, through the bushes, down towards the farm. But the fields had gone, and there was just a large space of wheat growing, and some plowed land, fallow and dark. I hadn’t intended to visit the farm itself, but as I went past the bottom of the lane, past the old stone-built stand where I had so often hauled up the full milk churns to be picked up by the milk lorry there was a For Sale sign stuck up at the gate. Without pausing to think, I turned up the lane. It had been winding, lined with flowers, blackberries, muddy and hard to walk without getting wet after rain, and I had walked it each day with the dogs, down to collect the post, or down to catch the bus along the main road into town. Now, the lane was just a track, no walls on either side, no winding curves to invite the visitor. I came out at the farm yard.

This was no longer a yard, or at least, it was no longer anything to do with a farm. The buildings still stood, and there was some kind of structure in the middle of the space, but there were small tubs of petunias dotted around and it all looked like some kind of municipal carpark. The old stables, still there but looking neat, and pretty in a magazine fashion, as if they had been created for a theme park not for real use. The milking shed had patio furniture standing neatly outside the door, and curtains shielded the windows where once the cats had perched waiting for their milk. It all looked the same and yet it was utterly different. A tall man came out of the house, wearing a buttoned down blue shirt, neatly pressed, and grey trousers, soft shoes and a mobile phone in his hand.

He was a retired doctor who had bought the house, with just a small piece of garden, about eighteen months ago, and he knew nothing about the history of the land or of the farm itself. He showed me around the house, and I could just recognize the rooms, the deep set windows, the view out over the fields towards Sennen. But the rest was new, done up, with the old house covered over by nice furnishing, comfortable carpets, proper heating and the kind of bathrooms that featured in design magazines. I thought of William, and then I remembered too our time in the house, carrying water, bringing in fresh milk and taking thick cream of the top of each jug, listening to the gales rage, going out in the rain to bring the cows in for milking, caring about each spot on the farm.. I knew that it was the same house and yet there was no acknowledgement that this had been a real, working place, loved and inhabited by generations of Tregears, and who knows who before them.

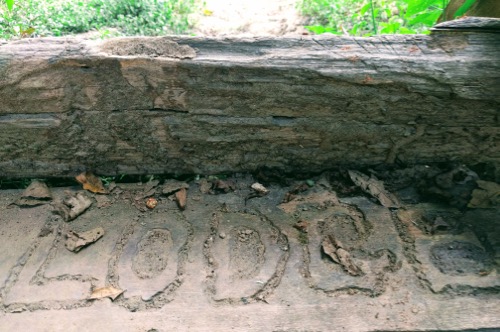

He showed me around, and then we went back outside. The barns on the other side of the yard had been bought, done up as holiday cottages, used for perhaps a month or so each year and rented out for sums of money that seemed unreal to me. The For Sale sign that had brought me up the lane was for the old pig shed, a small barn that had housed three litters of pigs at a time. It was freshly roofed, and the stone work pointed, cement making the walls neat and probably more solid. The front door could have belonged in a street of town houses, in some city far away from this windswept, granite grounded finger of land surrounded by the wild Atlantic.

Nothing I saw matched my memories. It all seemed as though a theme park had been constructed over the site of a prehistoric settlement: the displacement was as strong as if I had come out of the age of dinosaurs to find a new species occupying my own habitat.