https://www.eventbrite.com.au/e/classic-travel-writing-from-colombia-to-japan-tickets-1095842236629

Get your ticket for our first session on 19 Feb 2025 10:30 AM. All the details in the above link.

January 7

https://www.eventbrite.com.au/e/classic-travel-writing-from-colombia-to-japan-tickets-1095842236629

Get your ticket for our first session on 19 Feb 2025 10:30 AM. All the details in the above link.

December 10

As usual I look at the New York Times list of best books for this year and I realise what an alternative universe some people inhabit, and feel compelled to write my own 10 best books list. So here it is, as usual at this time of year. The jacarandas in Perth have been shedding their purple bounty across the pavements of UWA and Crawley and the undergraduates have left the library empty to quiet and to me. The weather is warming up and it is a calmer time of year, a time for reflection on what has been notable in my world of books. Many of these books are new, but as usual, I include some that were new to me but may be old to the world.

The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin (1987)

Bruce Chatwin didn’t actually spend much time out of his four or five decades on earth in Australia – so he is no expert on Australia and its cultures and landscapes. On the other hand his few weeks in and around Alice Springs in the early 1980s brushing with traditional Australians in the desert and recording a journalistic slice of their life does give him an insight in Aboriginal Australia I don’t have myself as an Australian. I think this comes from Chatwin’s immense confidence and sense of purpose as a travel writer. And that sense of confidence and purpose is something all of us writer’s should try to have more of – life is whistling by and if we don’t stand up from our desks right now and go and stride into our interests on the ground then history will pass us by. Thanks for this reminder Bruce.

But this book is of value to me more for its thoughts on nomadism. A large slab of the book is basically his ‘commonplace book’, his literary scrapbook, for fragments of writing, his own and others, that adumbrate why and how we humans are fundamentally restless and travel loving as a species. He recalls chatting with a nomad in the deserts of Sudan, and then quotes something about Cain and Abel from the bible, then gives us a bit of a letter by Flaubert. It is compelling stuff – for the same reason his best work is. He conjures the romance of travel through glimpses and images and mutterings, in the way only a mystically propelled and slightly misanthropic aesthete like Chatwin could do.

Material World by Ed Conway (2024)

Spend some time with this book and have your eyes opened to some of the miraculous substances that undergird modern civilization as it is enjoyed in the West. To give just one example, I will never look at sand in the same way again now knowing that it makes the glass for our digital devices and optic fibres. Conway is right to step back and take a clear and awestruck view of the materials that make up our world.

Explorer by Benedict Allen (2023)

In his early sixties, Benedict Allen reflects on his life exploring. He spend a good chunk of the 1980s and later doing adventurous solo walks through places in the Amazon and PNG, relying only on the help of local peoples. Seemingly the most impressive experiences he had were in the wild forests and on the banks of the Sepik in PNG. At some point he gave up exploring and got a family and a house. Years later, just a few years before this was published in 2022, he goes back to PNG twice and spends time with the same people he had visited in his twenties. In between Allen gives us plenty of bemused philosophizing about why explorers go exploring, as well as a few too many dismissive comments about Western explorers.

I enjoyed the book as he is describing places and situations – walking through warm tropical forests in PNG that I will probably not walk through, covered in leeches and, at the end, suffering from dengue and malaria. At the end of the book he is rescued by helicopter and instead of being profoundly grateful he tells us that he is not comfortable being saved. This all seems a little selfish considering as he was preparing himself to die in his journal a few hours before, and he has young children back in England. However he is appreciative of the traditional people of this place and is intimate with their world more than I will ever be. I enjoyed reading the book in that Allen could share some of that world of ancient Melanesian culture and its bird of paradise feathers in headdresses, its thick sense of community solidarity and its lost valleys and deep green forests where even the locals rarely if ever have been. Not a must read, but I was happy to read it as the shelf with recently published books about genuine exploration of my region is not a huge one.

Burmese Days by George Orwell (1934)

This year I read Paul Theroux’s 2024 novel Burma Sahib which dramatises Orwell’s time as a young man in Burma, and this lead me to pick up Orwell’s own roman a clef novel where the protagonist is pretty clearly Orwell in disguise. I implore you to not bother reading Theroux’s derivative concoction, and go straight to the original. Orwell is funnier than Theroux (perhaps the British sense of humour trumping American earnestness), and a few times I actually laughed out loud reading Orwell’s novel. He is also more concise and authentic in his descriptions of the seasons and fine grained details of colonial club lounges, tennis or shooting and other facets of the world he himself lived in (unlike Theroux who imagined himself into that world from a distant point in the future).

The protagonist of the novel is John Flory, a young man who has lived in Burma for his twenties and dealt with his loneliness by having a dog, a Burmese mistress, and reading lots in the evening. He is appalled by the racisim and bluster of many of the whites in the small town in northern Burma where he works as a timber merchant. But he is also appalled by some of the local Burmese he meets. His one true friend is an Indian doctor. This is another difference with the Theroux book – Orwell calls a spade a spade if he encounters cruelty and venality, regardless of which ethnicity the person exhibiting it has, which in Theroux the whites are generally the villains. The ending of Orwell’s novel dissapointed me – it is squalid and rushed (although I won’t tell you what happens in case you want to read the book). I enjoyed the novel for its reminder of what life is like as an expat living and working in Asia – of course this world is unqiue as it is the early twentieth century, with instituionalised racism in which ‘natives’ do the menial work and the British administrate.

But I empathised with Flory’s loneliness – I have sometimes felt marooned in a society where those around me don’t care deeply about literature, philosophy, art and other finer aspects of civilisation. Lonely in not being able to talk with friends about these things in a rich and stimulating conversational manner. I empathised with Flory’s feeling that many of those around him are not deeply interested in the cultures, arts, and ways of life of the people of south-east Asia. I empathised with Flory in feeling that the women he has courted in life have often not been particularly interested in the reflections on life you find in great books. Having said all of that Flory is an anti-hero – he is a coward at key moments in the novel. On the other hand he does show some bravery, and aren’t we all amalgams of the good and the bad, the resolute and the lazy, the righteous and the expedient? Crooked timber, feet of clay and all that. Orwell gives us an engaging trip into the world of the British raj in Burma in 1934, and apart from the unnecessarily grim finale, I enjoyed the journey.

Turn Up the Ocean by Tony Hoagland (2022)

A posthumous gift of ars poetica from easily one of America’s finest poets of the last twenty years.

The Genetic Book of the Dead by Richard Dawkins (2024)

Every now and again we will all find it salutary to rehearse the wonderful lineaments of biological evolution. Few people are able to take you through these wonders, one after another, as well as Richard Dawkins. Take the the time to go on what will probably be Dawkins’ final meander through the greatest show on earth.

Out of African by Karen Blixen (1937)

I have been to Nairobi – in 2017 – and this book enabled me to glimpse the world of that region a century earlier, long before the traffic jams and urban sprawl took hold. Particularly the hills outside the city. The world of the farm the author owned is beautifully described, conjuring up a different Africa, one that is a kind of pastoral idyll with its roots in a tribal world much older than the pastoral idylls of the West.

The Story of Art by E. H. Gombrich (1950, but this edition published 2023)

An intelligent and jargon free tour through the history of Western art. Reading this book for the first time I am reminded of how important it is to know our common Western culture, which is in part a history of paintings, buildings and sculptures which have meaning and beauty as they come to us across the centuries. I almost feel it is a duty to have some knowledge of Western civilisation in this sense if you want to call yourself an educated citizen and heir to the Western tradition. Most people seem content to take photos of their dinner and post them on Instagram, and for those people in this way remaining forever naive of our great artistic, architectural and literary traditions, our common culture of Western civilisation, I feel sad. They don’t know what they are missing out on. More than that with fewer people having an acquaintance with this common historical culture, society’s points of reference are impoverished, our conversations are hollowed out, and civilisation in this country ebbs and gutters like a candle flickering low. You can read this book for nothing if you get it out from a public library, but it enriches you in ways different and perhaps deeper than owning a new BMW and the latest smartphone. Of course as well as reading books like this it is ideal to spend some time wandering around places like Florence, Rome, Athens and Amsterdam and their galleries and museums (and yes, that requires more money, but it still doesn’t require you to be rich if you do it in the right way).

And after you have read this, watch the full series made for BBC, Civilisation (1969) with Sir Kenneth Clark talking to camera like an adult and you will further flesh out the story this book narrates so limpidly. (After rewatching this series I started reading Clark’s autobiography, Another Part of the Wood – what an entertaining memoir of an old school aesthete it is!)

The New Cold Wars by David Sanger (2024)

2024 is a time of enormous geopolitical tensions around the world, and particularly between the West and Russia and China. You would do well to know what is going on, because what is going on is actual history with a capital H. In steps David Sanger and his new book ‘New Cold Wars’. It is a gripping and detailed portrait of our times – far more useful and revealing than reading brief newspaper articles on these issues. David E. Sanger is national security correspondent for The New York Times – that means he was there and met the statesman or woman in question, year after year, rather than commentating from the armchair.

Tales from the Queen of the Desert by Gertrude Bell (part of which was published in 1907)

This book contains some of Bell’s writings on Persia, but also a long excerpt from The Desert and the Sown. It is this second work that most grabs my attention. It is an account of her 1905 journey through Syria – anecdotes from relaxing by a fire in a cave with various Bedu tribesmen and other ethnic groups like Druze and Christians. She communicates what the middle east was like in an earlier incantation I will never really know, unless I read books like this one. She clearly loves the people and the landscapes of this region. She died without a husband or children, but felt part of the great Arab world in the end, bint of the Arabs as one sheikh called her. This book brings you close to the soul of the place and for that it is precious.

August 27

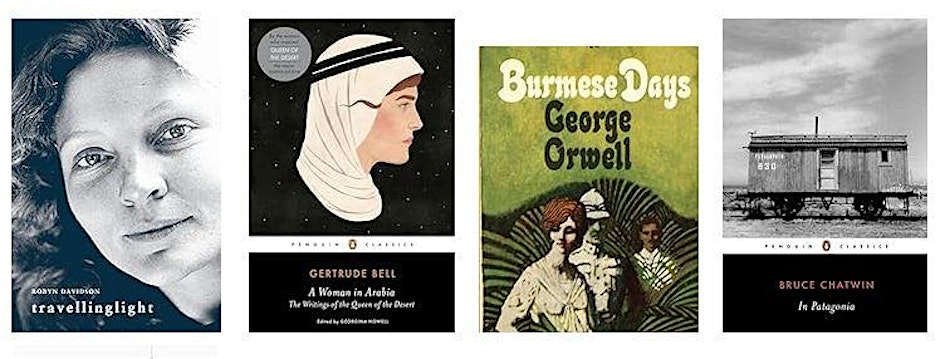

In this, my fourth course offered on travel writing so far, we’ll look at a selection of authors who have left home, and gone ‘elsewhere’ with their eyes wide open. We will look at extracts from two of Gertrude Bell’s most compelling works of travel writing, Persian Pictures and Syria: The Desert and the Sown, as well as some of her most fascinating letters, we will look at Bruce Chatwin’s exquisite account of his journey through Patagonia as well as his ‘commonplace book’ of quotes found inside his book Songlines, a selection from the Australian author Robyn Davidson, and George Orwell’s impressions of Burma in his fiction (as well as, very briefly, Paul Theroux’s 2024 pseudo-biographical novel about Orwell in Burma, Burma Sahib). We will consider the travel writer’s penchant for escaping conventional modern life in the Western world, and finding a sense of connection with people and the natural world in small scale rural societies far from home.

10.30am-midday fortnightly in Girrawheen Library’s Quiet Room.

11 September – Introductory lecture, housekeeping

25 September – George Orwell – Burmese Days

9 October – Bruce Chatwin – Extracts from In Patagonia and The Songlines

23 October – Robyn Davidson – Travelling Light

6 November – Gertrude Bell – A selection

The course is presented by myself in conjunction with the City of Wanneroo and the University of The Third Age (U3A) – Perth.

Please register your interest here.