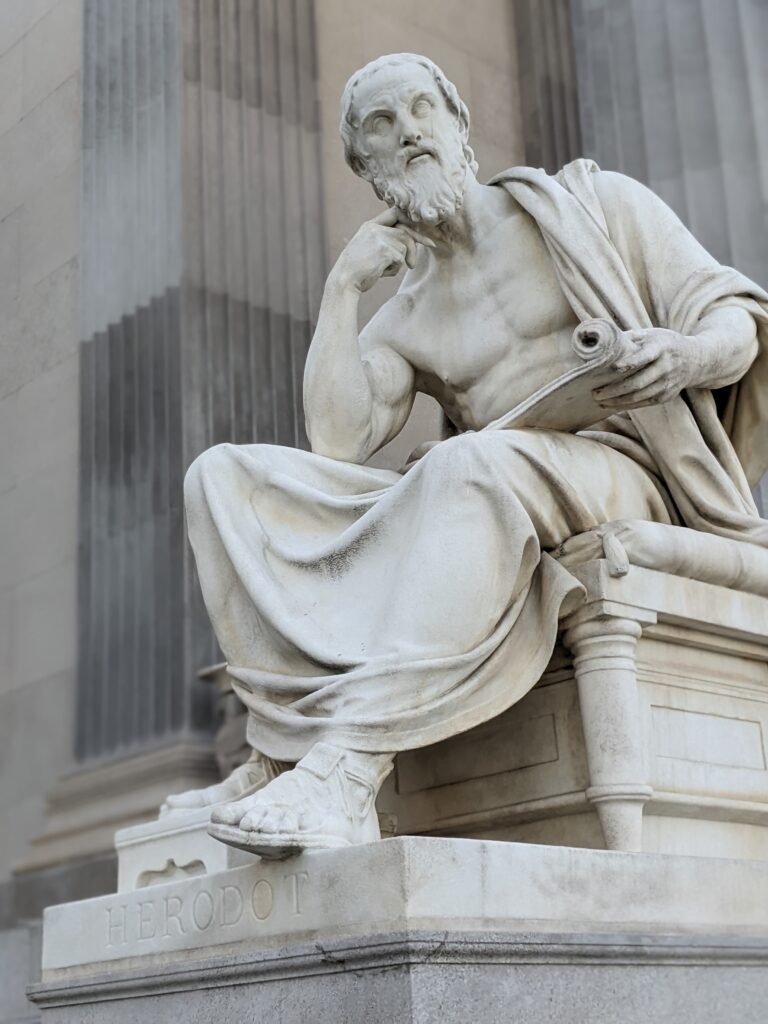

Is the image of Lord Elgin’s workmen sawing off a metope from atop the Parthenon in 1801 (see the painting below) just as bad as a shaky video of an ISIS fanatic sledge hammering an Assyrian sculpture into oblivion a few years ago?

Not quite, as the iconoclasts, be they ancient Christian or modern Muslim, just want to destroy, whereas Elgin wanted to enjoy – and he did ultimately sell them to a public museum where they could be viewed by thousands and now today millions. And at the time, the early 1800s, the Turks were treating the site of the Acropolis pretty badly – there were shards of the Parthenon laying around on the ground and a minaret sticking out of its roof. However it is still pretty shocking to think of – sawing through ancient marble, the metal saw rasping against the old stone, all so that you can stick the stone slab on a sailing boat and high tail it around Spain northwards, to the damp and chilly streets of London and Burlington House.

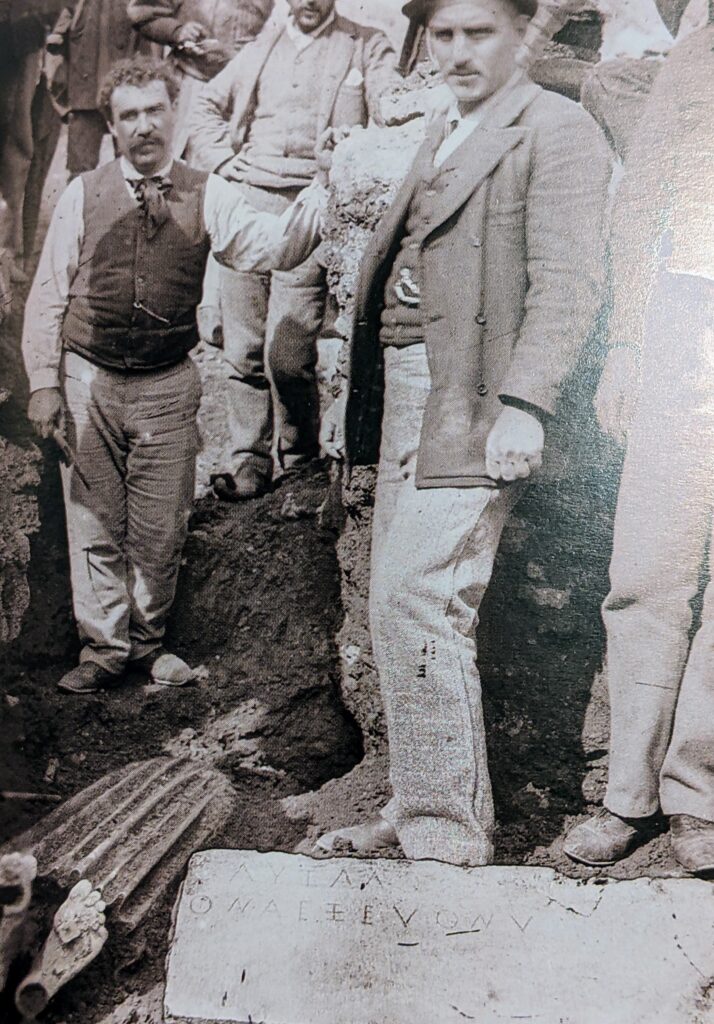

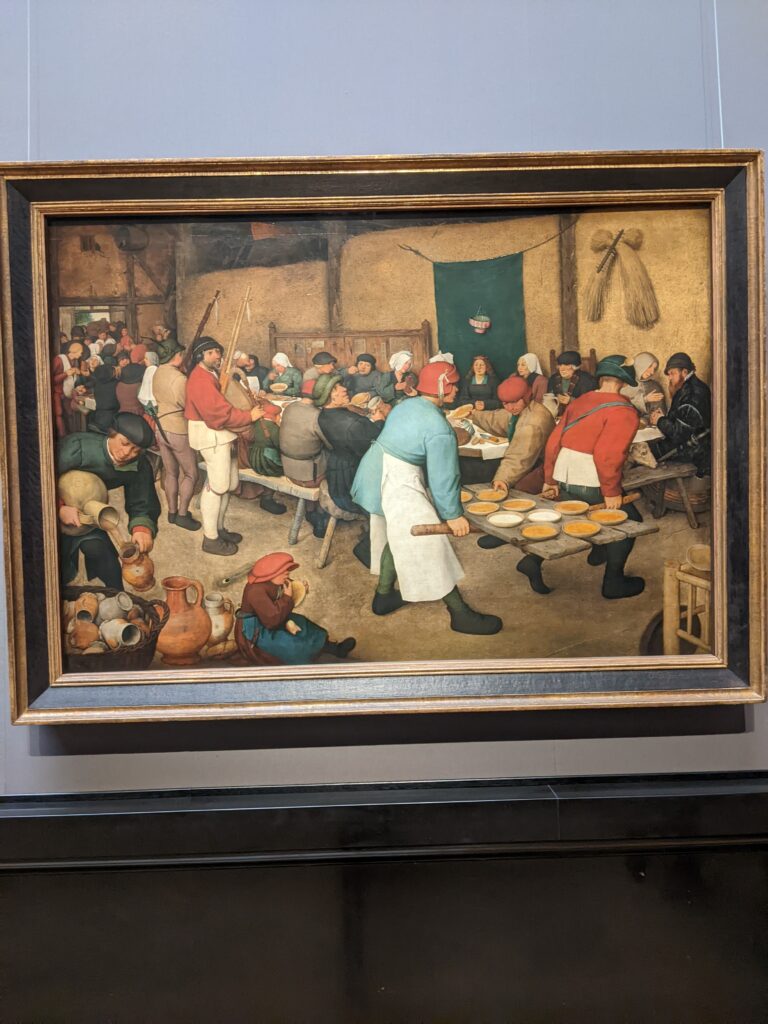

Lord Elgin was like so many British aristocrats – he wanted to own lots of beautiful and ancient stuff. He wanted to put said stuff in a big house. You see it again and again, from Hertford House (today’s Wallace Collection) in London, to the Earl of Bristol’s Ickworth House in Suffolk. A Florentine pietra dura cabinet here, a Roman sarcophagus carved from marble there, a Brueghel canvas here, a full size Greek bronze figure there. This impulse to own was part showing off, part investing their huge wealth in objects and I’m sure also, at least in some cases, part actually appreciating beauty, craftsmanship and history.

‘Money has reckoned the soul of [the nation]… /…all Owners, Owners! Owners! with / obsession on property and vanishing Selfhood!’ (Allen Ginsberg, from Death To Van Gogh’s Ear). The urge to own stuff can end up imprisoning you, as Ginsberg intimated in this line. Focus too much on possessions and you start forgetting about the fragile living present tense, relationships and the wild earth around you.

Since I have been a nomad in 2023, just a few clothes and a phone and a wallet, and some strong walking legs, moving across Europe, I have felt quite free. Walking around a bend in the rocky path around a spur of the coastline on Hydra yesterday I felt free. It was just me, moving, unencumbered. Objects didn’t own me, or drag my motion through the world. An externally imposed routine didn’t own me either.

It is possible to be at the mercy of one’s possessions. Being a nomad, being a traveller, can liberate you from this tyranny of things. Walking, free, and unencumbered by possessions. Walking yourself happy.

What should we think of Lord Elgin’s sawing off the sculptures of the Parthenon, and the urge to pillage and hoard beauty and tangible history that many rich English chaps have followed through on over the centuries? This question is usually answered in terms of should the sculptures be returned to Greece by the British Museum, and that is a valid topic, but I am obviously focusing on a different aspect of the subject. I think that being obsessed with owning and hoarding nice stuff in your big English country house, or even your modern apartment, can get in the way of living. It can be an obstacle to enjoying the fragile, living moment. All we get in this life are a finite number of living moments, and then we disappear from the earth forever, like the Venerable Bede’s swallow flying into the warm mead-hall and out another door in an instant. Of course many of us enjoy owning nice stuff. Freud was a man who hoarded nice antiquities. Bruce Chatwin the nomad renounced his former life selling nice stuff for Sotherby’s and extolled the virtue of moving lightly as a nomad.

For a long time I thought that it is perhaps good to remember the way of the Bedu of Arabia – rich in space and relationships (ok they liked to have a few camels too!). That way of thinking makes you younger I felt and gives you more possibilities in life. I am interested in history and art, but like Chatwin and others, I am wary of the way stuff can come to own you.

I was on Hydra on Friday, a mountainous island a couple of hours south of Athens on a ferry. The outrageous sum of $126 AU dollars for the ferry trip indicates that Hydra these days is for the rich, not for the bohemian poets and song writers it hosted in the 1960s. There was a cruise ship in full of wealthy and overweight Americans and the crowds on the dock were thick. All of that said, I still managed to walk away from the town along the coast and after a few kms I found a stretch of rocky coastline dropping into deep blue water and went for a swim, blessedly alone, free from the mass that has surrounded me of late.

And in the late afternoon I bought a beer from a supermarket and sat on the dock, down a few steps by the fishing boats were tourists don’t go, and dangled my feet in the cool sea water and looked up at the scene of Hydra town. The white cube-like houses hug the dramatically rising bay’s slopes, creating a kind of amphitheatre, topped by arid hills, stones and bushes. A stone tower of a church rises in neoclassical elegance to the right in the front row of buildings along the quay. Brightly painted little fishing boats float in the water in the immediate foreground. It is a beautiful scene. The shadows of the lengthening sun fall over me and bring relief from the thirty degree heat of mid September. I feel a warm beneficence to the world, the water gentle on my skin, the human settlement so pleasingly nestled into the land, a sense of uplift from seeing the powerful, rocky mountains above, my walking over. I rest and feel the freedom from care and mild cheerfulness that a cold beer brings one’s perspective. A pleasing symphony of elements that a Greek island without cars can bring. My selfhood is restored.