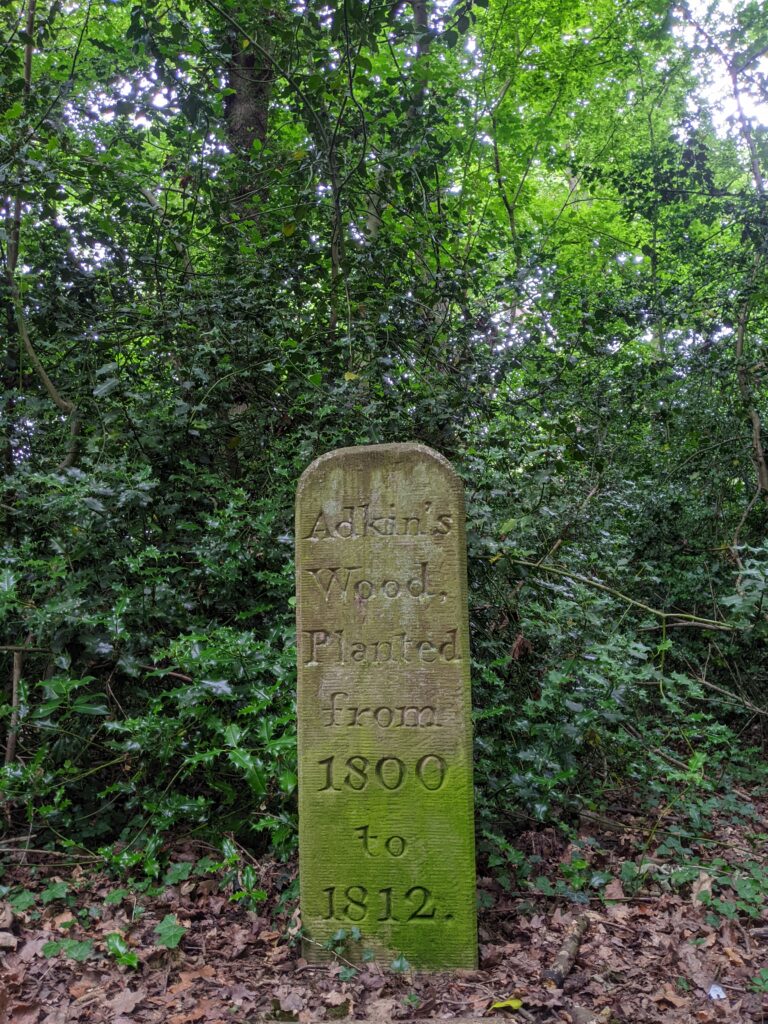

The next day we drove out to Ickworth House in Suffolk to the east of Cambridge. We parked outside the grounds of the estate by an old country church. Walked through the grave stones of course, and into the church. Visiting out of the way churches in the countryside is something I am quite happy to do (perhaps odd as I’m an atheist, but they are still great Houses of Seriousness) . Then through the main gates into the estate, and veered left into the woods. Green leaves and old oaks enveloped us immediately as we walked down the winding dirt path. An eighteenth century stone’s carvings informed us that this was Adkin’s wood. I could tell that we all felt refreshed by being in this forest with its ancient, tall trees and mysterious vistas. Then we burst out of the forest onto the wide, open parkland, dotted with many century old oaks. These oaks were lustily uttering green leaves to the heavens, thickly limbed and massively girthed. Onwards, and closer to the house, although we couldn’t see much of it yet. I knew of Ickworth’s great central rotunda, more at home in classical Rome than the Suffolk countryside, so I was looking forward to seeing it. As we rounded the path along the east wing of the house the huge rotunda came into view, and we were suitably awed. We walked closer and could see the bas reliefs of scenes of battles and other events from ancient Rome, ringing the rotunda. A bold expression of the love of antiquity by the marquesses of Bath deep in the green and rural heart of Suffolk. We entered the house after a coffee and cake in the National Trust café, and came into the presence of a huge atrium at the centre of which stood a big white marble sculpture taken from Italy long ago. Walking inside the principal drawing room of the house I saw bookshelves atop which stood marbles busts. Two of them I could identify as Alexander the Great and Homer. The dining room had canvases on the walls with three metre tall members of the family looking down confidently – what colossal self-importance these aristocrats cultivated through art works commissioned of themselves.

The Earl Bishop who had conceived this rotunda as a place to display his art collection from a grand tours of Italy lost all his booty to Napoleon’s troops. His son managed to buy back during a four year grand tour of Italy with his family much later. So at least the great sculpture which graces the entrance atrium, ‘The Fury of Athamas’ by John Flaxman RA (York 1755 – London 1826) is where it was intended to be. Interestingly a descendent (who had been a jewel thief in Mayfair mansions among other things) gave the house to the state and thus the National Trust in 1956, and his son took heroin and lost a 21 million pound fortune on high living and, ultimately, lost his lease tenure in Ickworth (and then his life). Five centuries of family association down the plug with this last scion in the late 1990s when he died from an overdose.

We wound down on empty little country roads through Suffolk, over its gently rolling hills and quiet valleys. Eventually arrived in the little village of Long Melford. We were there to see Melford Hall, built in the 1400s and ransacked by the puritans in the civil war. Added to by a few different families, it sits on its smooth green sward with stately red bricks, mellowed by the centuries and the weather. What a different vision of a stately home to Ickworth. This I much preferred. This was a grand house in an earlier era, when ancient Rome wasn’t the fashion, and English red brick towers and medieval style halls were more common. The interior of the house is full of remembrance of the family that lived here until not long ago – the chairs don’t have little ropes to stop you sitting on them (although you still shouldn’t), and family photos still sit on table tops. The dark wood hall you enter first is the quintessential version of English country house style from the Tudor era. The library is superb. Upstairs the bedrooms are ones you could imagine sleeping in at a weekend party in the Edwardian period – comfortable and human sized and lived in, but still with touches of elegance and style. The way the upstairs corridor kept unfolding more and more rooms reminded me that this was indeed a grand country residence, if still humble compared to Ickworth House, or the great (read bombastically gigantic) country houses of England such as Chatsworth and Blenheim. Melford Hall is for me the essence of what I love about the soul of England – a mouldering old country house with layers of history and love and loss and art and wood, surrounded by quiet, green gardens and gently undulating parkland beyond. And owned by the people through the aegis of the National Trust. Not a hint of the twentieth or twenty first century to be seen. All that is gone. What this trip to England taught me is that the old England I love is still there, and without too much effort, just getting out into the country side with a hire car and a National Trust pass, you can experience it still. How nice it is to know that the England I love is not critically endangered or extinct. Of course you need to skip the famous country houses such as Blenheim, and go to places like Melford Hall. Go somewhere that is not famous, somewhere that doesn’t trip off the tour guides lips and is out in Northumberland or Essex or Dorset or Shropshire. But that’s easily done.

Later that day we walked up to Kentwell House, pass the parish church, over a sty and through a green field. As the others walked ahead I looked back over the hills of Suffolk stretching away below, church spire rising about the copse of trees in beyond the field and hills beyond that. It was a long summer’s evening and the sun was still warm. And I imagined walking this same hill and seeing this same view in spring, and in autumn. In winter and summer. The poetry of this place, the soul of this place. It made me feel deeply moved by the beauty of England.

And then to the village of Long Melford and to Melford Hall…