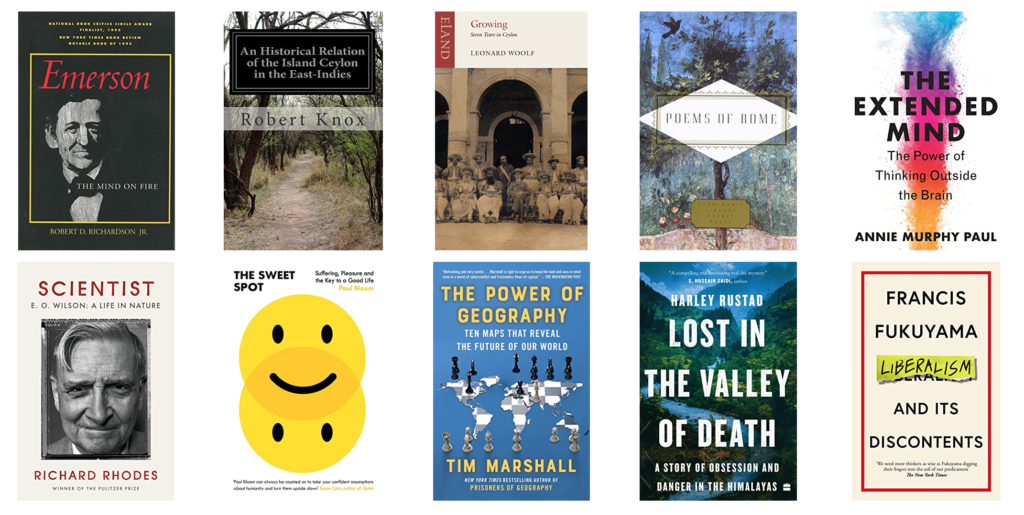

I will start with a few books that were favourites from my year of reading and then concentrate on notable books published in 2022. Biography, autobiography, poetry, philosophy, politics and travel writing are all genres that made my list this year.

Robert Richardson has read just about everything that Emerson read, so he’s able to contextualize periods and ideas in the author’s life and writings in a very helpful manner. He writes superbly, and he really gets Emerson’s impulse to praise and celebrate. Emerson distributed his literary largess in journal entries, letters, lectures and elsewhere, so by reading biography you get in effect a lovely ‘selected Emerson’. And Emerson at his best is, in my view, as good as imaginative prose ever gets in the English language. Having this book in my life for a few weeks was galvanizing, and a reminder of why I am passionate about literature.

(First published 1995.)

One of the great travelogues and adventure stories of autobiographical literature. After describing the manners and attributes of the locals from his decades living in 1670s Ceylon in the mountains, Robert Knox recounts his escape and journey north. The reader can imagine this journey, sleeping in the open where wild predators roamed, and making his way forward down river beds and along river banks and through rainforests. A glimpse of a truly lost world. Why hasn’t this true story and insight into ancient Sri Lanka been turned into a film?

(First published in 1681.)

Playing tennis with starched whites with the other English administrators and then chatting over gin and tonics in the tropical warm of the evening in an old Dutch fort on the north-east coast of Sri Lanka in the first decade of the twentieth century… Getting to know the Sinhalese of the Kandy region through hearing their complaints, intrigues, and travails in their own language as a defacto judge… As I read through this memoir I felt like I was sitting around the fire with Woolf in his last years (back in the sixties I think) and hearing stories from an educated, unconventional and honest English chap about a life lived in the twilight of the British Empire in Ceylon. And getting to know the Sri Lanka I’ve visited myself a few times better through hearing about the life and culture of people prior to much modernisation that took place over the twentieth century. Worth the price of admission for me.

(First published 1961.)

Some beautiful responses to the city of Rome, form Byron and Keats and Rilke to James Merrill, Derek Walcott and A. D. Hope. A. D. Hope’s ‘Letter from Rome’ is one Australian man’s encounter with the caput mundi, what was once thought the centre of the civilized world. This encounter unspools in humorous and digressive stanzas full of echoes of Byron’s Child Harolde’s Pilgrimage to this same city centuries earlier. I could quote any stanza but here is one that reminds me of my own trip to Rome this year:

Meanwhile I walk and gaze. For all its size,

Rome is a city one can see on foot,

And that’s the pace for such an enterprise.

Each morning we buy cheese and rolls and fruit

And stroll and stop to view whatever lies

Along a vague and ambulating route

I miss a lot of course, but what I see,

Because I found it, seems a part of me.

(First published 2018.)

Much of this book reads like chapters which hoard together the results of various scientific papers Paul has read in order to construct an argument. In other words it is heavily second order and derivative. However it is very worth reading the Conclusion. Here she summarises the ways in which we are well served by thinking of the mind as functioning not like a machine or a computer, but rather as an organ which is made smarter by its extensions in the physical and social contexts in which it is embedded. You are smarter in beautiful natural settings, you will think more clearly in your lovely wooden panelled office, you will be aided by writing a journal as a way of making your thinking an artifact in the outside world, teach face to face in a social setting as a way of learning…

This way of understanding the mind has an interesting corollary for me. Which is that the spaces we live in will motivate us more if they are beautiful and personally meaningful. Architecture and design are not just frills, as the ancient Romans and the English aristocracy knew. Louis Kahn the American architect said, “If you look at the Baths of Caracalla … we all know that we can bathe just as well under an eight-foot ceiling as we can under a 150-foot ceiling … [but] there’s something about a 150-foot ceiling that makes a different kind of man.” Its strange as recently I had been looking at images of the original Penn station in New York as it was modelled the bathes of Caracalla. Its an enobling space with its vast pillars and 50 metre tall coffered ceiling and it was a tragedy that they knocked it down in the sixties. I was having a shower at my gym in my little shower cubicle and closed my eyes and imagined being in a cauldarium (hot tub) in the Roman thermae instead, perhaps regarding a marble statue of Hercules as I soaked in the warm water and chatted with someone.

When I read the above quote by Kahn I thought: that’s it exactly – that ‘makes a different kind of man’. Taking the concept of the extended mind seriously will make us take the spaces we think and work and relax in more seriously and not just as interchangeable units and backdrops.

(First published 2021.)

I was by turns heartened by this book, and dissapointed. The first because it helped me revisit the world of natural history discovery, courtly and warm Southern charm of the man himself, and deep belief in the value of searching and reflective scholarship on both the little things of this planet such as ants and the big questions that encircle us existentially. The author Richard Rhodes has not written a biography that measure up to the man though – it seems plodding and pedestrian in parts. Enumerating his achievements for example towards the end. You feel a distance between Rhodes and Wilson. Still its better than not having any biography of Wilson. With Wilson’s passing this year – 2022 – I needed a way to honour his memory and significance in my life, and reading this book was better than nothing.

(First published 2021.)

Towards the end of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World we read these lines: “But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin. “In fact,” said Mustapha Mond, “you’re claiming the right to be unhappy.” “All right then,” said the Savage defiantly, “I’m claiming the right to be unhappy.” This is the perfect coda for Paul Bloom’s book The Sweet Spot.

The book explores how it is that people so often pursue projects that involve suffering. In fact it comes down in part to the fact that humans don’t just want comfort and happiness in the purely hedonistic, momentary sense of floating in a swimming pool. They also want a sense of meaning, and often this comes from caring for others for example. Bloom sides with John Stuart Mill where he writes in Utilitarianism: It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, is of a different opinion, it is only because they only know their own side of the question. If you have not watched ‘Moralities of Everyday Life’, Bloom’s lecture series he recorded from Yale for Coursera, you should do so. It is excellent. In this book as in his lectures Bloom continues his highly approachable and good humoured style of philosophy. He like, Johnathan Haidt does a kind of philosophy that circles back to the evidence-based realities of human psychology, which makes it much more relevant and interesting than other more hand waving styles of philosophizing. Not a must read book, but interesting nonetheless.

(First published 2021.)

Sometimes I wish that I could have the equivalent of the Economist magazine’s coverage of the world condensed and given to me once a year, including historical background I’m ignorant of about a region such as say, Turkey. This book is exactly that. Refreshing to have someone like Marshall call a spade a spade in the world of geopolitics, rather than hide behind elaborate and obfuscatory sentences in the ivory tower. I felt compelled to keep reading because of his bracing pace as he passed through Saudia Arabia and its politics and history, Iran, Turkey, the Sahel region, etc.

(First published 2022.)

First the reservations, then the praise. This is a work of ‘true crime’, and like most of that genre of popular writing does not reach the realms of memorable literature. It follows the life of Justin Alexander, an American born in 1981 who was a survival expert, and rootless wanderer, and who went missing in 2016 in a forested valley of the Indian Himalayas, probably murdered by a sham holy man he had befriended Justin documented his adventures on Instagram, and seemed self-obsessed and narcissitic, flexing his biceps while he wrote motorbikes up the West coast of the US, or climbing trees on Palawan in the Phillipines. He was not articulate or eloquent, and reviewers who liken this book to Somerset Maugham for the age of the hashtag miss that point entirely. Even the author Rustad is not a Bruce Chatwin or a Robert Louis Stevenson in terms of the quality of his prose, following this nomad.

Now the praise: Justin watched and was inspired by Baraka the film as a young man and his model of spiritually questing travel and attempts to live vividly speak, for me, of all the ‘seeker’ style travellers one has met over the years. They may not be eloquent or highly educated or particularly humble, but they have a fierce appreciation of wonder and adventure, and this is refreshing to be around. There are many travellers like Justin, and for me this book is interesting in that it puts one such man in the frame for the reader to contemplate. He has probably died and while he lived he may have sometimes or often felt lonely on his journey, but he did not allow life to become humdrum, tawdry, trivial and banal. He did not allow life to seep away in nine-to-five safe domesticity. For all of the people like him, who go forth and adventure to places like Thai villages or Brazilian forests, while never entering their accounts in the world of literature, and leaving a flotsam of social media posts at best, this book is a tribute. It was good to be reminded of such people at the end of two years when almost none of us in Australia had been travelling outside the country.

(First published 2022.)

In not much over 100 pages our modern master of succinct overviews of political structures manages to give us a manifesto for Liberalism. Thank you Fukuyama.

Both the extreme right (not prescriptive enough on common bonds) and the extreme left (too universalist in its presumptions) dislike liberalism, but the author demonstrates how both of these sides of politics exaggerate what can be valid points. Liberalism is still the best option around for modern national states like Australia and I can’t think of a better time to read such a precisely stated and strongly argued case for this version of ‘Progress’ through moderation.

(First published 2022.)