Last week I was riding a bike through the forests and lakes of the countryside outside the small village of Steinhagen. The fields of wheat stood tall and thick and ready to harvest, and were bounded by forests of oak, heavy with clambering wreaths of ivy. A lowering sky of grey but lambent cloud hinted at rain to come, but a deep rural calm lay over everything. As my bikes wheels rolled along empty laneways and paths, I felt like I was deep in the heart of Europe. Small German red brick farm houses with steeply pitched roofs and half timbered walls peaked out of the wheat or corn fields. Occasional horses munched beside ancient stables. Hardly a soul was seen. It reminded me of a painting by Samuel Palmer, fields pregnant with significance, even if you weren’t sure what kind of significance it was.

Then over the weekend I walked around Heidelberg. The old city sits in a wooded and green valley of the hills that create the eastern side of a wide flat river basin through which the Rhine river runs north away from the Alps, far to the south. In this wooded valley Heidelberg lays along the river. Where Heidelberg’s old town is located at the eastern end of the city the slopes of the valley out of which the River Necker flows (a tributary of the Rhine), become very steep. The city can’t expand into modern suburbs here as there is no space, there are only old buildings, wooded slopes and the quietly rolling River Neckar. Yes there are plenty of tourists on the old bridge, but many of the streets are still quiet with the occasional bicycle or passing university student. Over tourism isn’t overwhelming here. The castle on the hill has been a partial ruin for most of the past two centuries, and was admired for its picturesque location high above the city and nestled among chestnut and oak trees by Mark Twain, J. M. W. Turner and other romantic visitors, painters and poets throughout the nineteenth century. Walking up the hill to this castle I was reminded of walking up the hill to the Alhambra: a steep and heart quickening stride up a cobbled lane through deep green trees to an ancient fortress high up above you. The red sandstone that the castle of the castle’s walls makes for an unusual sight. And from the windows, arches and terraces of the castle you look down and over the River Neckar, over the arches of the old bridge crossing it, to the other side of the thickly wooded valley, with a few nineteenth and eighteenth century mansions lining its further bank. Above the mansions is a line through the woods, and that is the Philosophenweg (the Philosopher’s Path), along which generations of university professors and philosophers have walked, cogitating loftily high above the waters and the city.

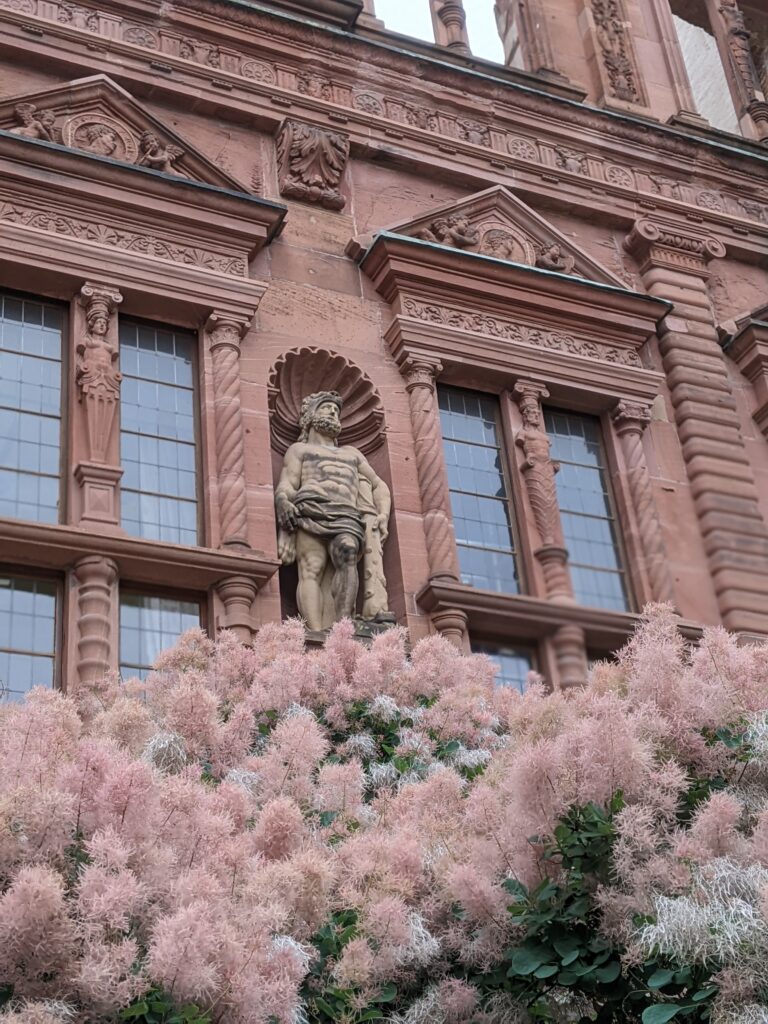

The city’s university library is another building in red sandstone. Walking through its front entrance is a lesson in dignity, gravitas and beauty. If only all library’s imparted such lessons in stone to those passing through their portals. (I should know – often they don’t!) This is a university library that tells its students that you are in an important place, a hallowed place. Heidelberg University, incidentally, was the model for the modern research university in the United States, first kicked off by John Hopkins in the late nineteenth century at its founding in the 1870s. Earlier in the day I had entered the Jesuit Church of Heidelberg. I have previously had little interest in baroque Catholic German church architecture – generally I find it overly artificial and it leaves me cold. However this church, with its tall white nave and glass crystal chandeliers, and small touches of green and cold colour at the top of the capitals of the pilasters on the nave’s piers, did touch me. The organ was playing beautiful descending notes, and the place was illuminated by a pure light everywhere, with only a small handful of worshipper and tourists wandering through.

Tomorrow I leave Germany, but I’m glad to have come if only for a few days.