I live in the south-west corner of Australia. The Nyungar people in this area spoke a mutually intelligible language, and unlike the people out in the more arid parts to the north and east, did not practice circumcision. The bioregion in the south-west corner of Australia can be considered as fitting into a space on the map that correlates neatly with the cultural bloc that used to inhabit it. But over the bulk of inland WA, east and north of Perth, is another bioregion, and lived another cultural bloc. These were, and are, the Western Desert people.

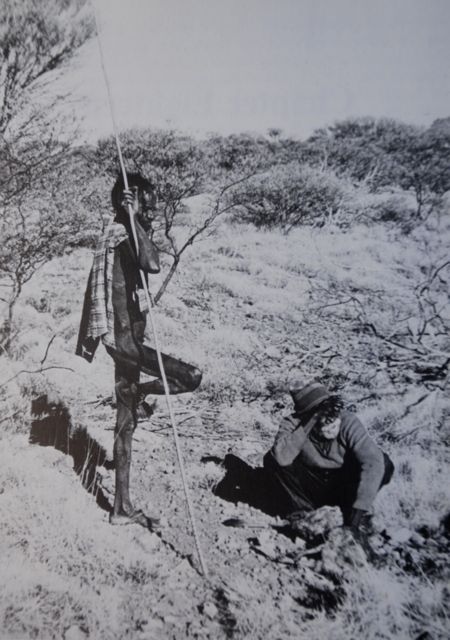

This is Yarri and his friend Mujon. Look at how straight Yarri’s spear is. It used to be a small, thinly trunked tree, but Yarri has placed it over a fire and turned it in his bare hands – full of sand to insulate his skin against the heat – and created this marvel of outback symmetry.

But to continue… Functioning Nyungar culture basically dissapeared many years ago, back at the end of the nineteenth century. However, in 1984 a family of nine who constituted the last uncontacted nomadic Aboriginals in Australia were brought out of the Gibson Desert in the north-west. It pleases me to think that during some of my time alive there have been traditional Australians living and hunting on the land exactly as their ancestors had done thousands of years before them.

However here I want to go back slightly earlier: to 1976. In 1976 some more of the last of the truly traditional Australians walked out of the Western Gibon Desert. They were an elderly Aboriginal couple, Warri Kyangu and Yatungka.

Many years ago this couple had married across blood groups and against the laws of their tribe. They had sought refuge from the legal repercussions of this act (a spear flying at them) by retreating to the most remote parts of north-west Australia. However there had been a severe drought and some of the Aboriginals in Wiluna feared for the survival of this couple, known to exist by some of the elders in Wiluna. So a search party was sent out. W. J. Peasley was a member of the search party, and wrote a book about his experience of being on the search party that finally made contact with the old Western Australians and brought them back to the white fellas world. The book is called The Last of the Nomads (Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 1983). It is a sad book. The couple were very frail, having lived almost exclusively on quandongs – small, sour tasting berries – in recent times. They knew their world: they knew the night’s sky, the warmth of their dingos as they lay close to the smouldering embers of their fire through cold and clear night’s in the desert. She knew how to find quandongs and lizards and how to shell and grind acacia seeds. He knew how to make almost three metre long spears that were as strait as an arrow, and how to throw them with pin point accuracy at fleeing kangaroos. They knew how to find rocky pools and water holes in the middle of the baking desert sands. They knew the laws of their tribe, long since left. Most of all they knew love for each other.

Like most of you I’m pretty helpless, hopeless and incapable when it comes to finding my own food, water, warmth and shelter outside the walls of cities and towns. Like most of you reading this now, if I was to walk off into the world of Warri Kyangu and Yatungka I would be dead in about three days.

Through neuro-plasticity your environment and your culture has a role in shaping the patterns of connections in your brains. Each day of their life this man and women interacted with Western Australia, with its textures, its ecology, its gait, its temperatures, its sands. This old man and women knew Western Australia better than I will ever know it. It humbles me to say that.

Before leaving their land they were told to leave their dingos behind as they would be classified as ‘vermin’ in station country. You can imagine how it must have felt to have to leave some of your family behind. Then when it came to climbing into the vehicle Warri became very frightened: ‘He was clearly terrified, making feeble efforts to climb up but he trembled so violently that he was forced to abandon each attempt’ (p.94). Warri was a seasoned and proud old man. In his world he had wisdom to offer. But in front of a Range Rover in 1976 he was reduced to shaking uncontrollably. What was going on here?

We can never know what is was like for Warri to climb into this vehicle. But let’s imagine it was like a seven foot tall albino African reigning up a pulsating, glowing beast with the texture of firm jelly in front of your house, and then being asked by this bizarre stranger to immerse yourself inside this creature’s gut before going on a trip some place you’ve never heard of. Would you do it? Would you climb into the gut of the beast? Would you perhaps start to shake uncontrollably because this was like something out of a bad dream, except that the sun was up there in the sky shining down on you, and your wife was there next to you, and it wasn’t a dream?

This moment, the moment that Warri tried to board a Range Rover in 1976, is one of the saddest and most poignant moments I know of in Australia’s photographic history.

On the trip back they made stops and every time the party got back into the vehicle Warri has difficulty getting onboard. During the night on their trip back to Wiluna they were camped by a fire. Although it was a cold night Warri and Yatungka shed the clothes they had been given by the party. The Aboriginal man who was on the party reported that: ‘they felt uncomfortable waring the white man’s shirts and trousers and with their several small fires, were quite happy to sit naked as they had done throughout their years in the desert’ (p.109).

In the following months back in Wiluna the author writes that: ‘Warri did not appear to comprehend what was happening to his people. He saw that much of the ‘law’ was openly disregarded, especially by the young, the social organisation was disintergrating rapidly and the widespread abuse of alcohol was destroying the self-respect and self-reliance his people once possessed…

Warri and Yatungka seemed to be reasonably happy, never openly expressing any desire to return to Ngarinarri. Warri rarely spoke, content to sit for long periods of time before his fire, whislt Yatungka, as she overcame her shyness and her fear of tribal retribution, took a more active part in the affairs of the people. She never moved far from her husband’s side and when engaged in conversation with others would, from time to time, reach out to touch Warri as though to reassure him that she was near, that he was not forgotten’ (p.117).

Warri clearly had culture shock. Through neuro-plasticity our brains change configuration to some extent in response to the particular culture we live in. When we move rapidly from one culture to another one which is very different from the one we came from we can experience a palpable sense of disorientation that we call culture shock.

The couple lived for one more year after leaving the desert before they died. On many night’s along during their years in the Gibson Desert Warri and Yatungka would have given huge solace to each other. They loved each other, it must have been this that made them break tribal law and to chose to live with each other in exile. In this bizarre and alien world away from their homeland Warri sat crossed legged on the sand, looking into the hot embers of his fire while others talked around him. He clearly didn’t understand this new world and felt shut out. The image of Yatungka reaching out to touch Warri while talking to somebody else, just to reassure him that she was still there, touches me.

From one ancient and sandy world in the Gibson Desert to a new and violently disorientating world in a hobbled together white fella’s brick and tin encampment one thing endured, one line of continuity ran strong: The quiet love between an old man and an old women.

really enjoyed your extremely interesting article – these ‘last’ people are very special