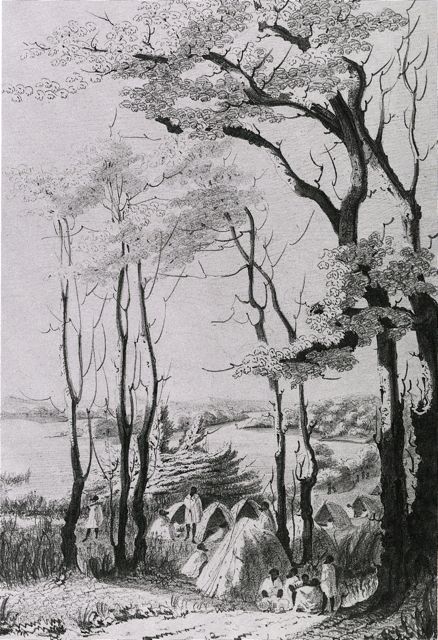

The sketch by Richard Ffarington was done along the edge of the Swan River in the 1840s (from Ffarington’s Folio: South West Australia 1843-1847, Art Gallery of Western Australia, 1986, p.26). It is a very rare glimpse into what Perth has meant for humans for the vast majority of the time humans have been here.

It is wrong of one nation to go and claim a part of another nation as as part of their country. Yet that is what the British did where I live in south-west Australia around a hundred and thirty years ago.

Langoulant, 1978.

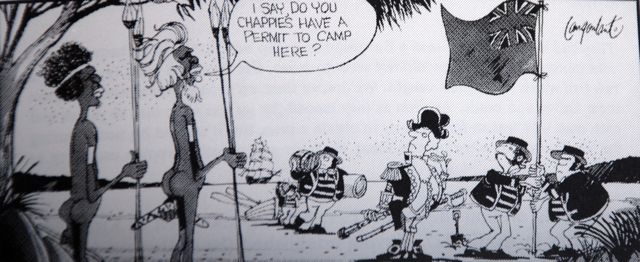

Early white settlers in Perth dismantled fishing traps and weirs of the Aboriginals, shot their dogs, and took their most valuable hunting pastures. They then flew the Union flag on the land, and told themselves that ‘the natives’ were a lower race of humans than ‘civilized’ members of the British Empire like themselves (‘civilized’ fellows were of course quite civilized enough to die from scurvy rather than eat nearby quandongs). It all reminds one of the arrogance and madness of tiny troops of Spanish men clambering through South American jungles in the 1500s and proclaiming ‘all this’, as they surveyed another grand vista of beautiful, green forest canopies, as belonging to the Spanish crown.

The banks of the Swan are full of interesting plants like balgas, or grass trees.

The shapes of this country are many oceans of difference away from the hedges and oaks of English fields…

When Captain James Stirling was exploring the Swan River in 1827 he didn’t have an SLR hanging over his shoulder, but he did have a professional artist with him: Frederick Garling. This is Garling’s version of what the banks of the Swan looked like as Stirling and the men explored up it. Here are the men rocking in their hammocks in the warm night’s air in a clearing, one that was probably used by Aboriginals as a campsite:

In 2009 the banks of the Swan look quite different. Now people who can’t tell the difference between a tuart and a jarrah bed down for the night in surburban monstrosities that have erased the character of the Australian earth.

Ah… the green Sahara of the lawn. The Perth metropolitan area has plenty of facilities for automobiles and demented suburban hubris, but not quite so many for ecological-niche dependant biodiversity. As Irene Cunningham says, in Perth ‘green lawns and football are seen as more important than saving the land’ (The Land of Flowers, 2005, p.34).

Jarrah trees of immense size were once common around Perth (full of nesting holes for Twenty Eight Parrots and other local life). This photo is of a Yanchep road scene from 1935:

Most of the big old patriarchs like this one were cut down for timber. Although there are a couple of exceptions like Bold Park and King’s Park, you could basically summarise the environmental history of Perth by singing along with Joni Mitchell: ‘They paved paradise and put up a parking lot’.

Many people in Perth have gotten rich through investing in the mining of their state. Many flaunt their material status symbols. These same people might heed the words of Clive James from his recent ‘Point of View’ broadcast on the BBC (2 Jan, 2009):

‘Getting rich for its own sake looks as stupid as body building does at that point when the neck gets thicker than the head, and the thighs and biceps look like four plastic kit bags full of tofu.’

The Perth metropolitan area keeps growing outwards, knocking down the tiny patches of banksia woodland we have left on the Swan Coastal Plain. Today central Perth is an unremarkable, steel and concrete central business district with a non-residential core, surrounded by sprawling, car and fossil-fuel dependent suburbs. But Perth wasn’t always this ugly or badly designed. Perth was a small town from the 1830s till the gold rush of the 1880s and 1890s turned it into a small city. It was up until the 1940s that it had two and three story Victorian architecture lining long streets like St. Georges Terrace and Hay St. This was the city of English values 13 thousand kms from England that my grandmother was a young woman in. It looks much as the West End of nearby Fremantle looks today, except that it has lovely little trams rolling up and down the street.

It is fascinating to think that for my grandmother this was her experience of Perth as a young woman: genteel Victorian stone facades, expansive balconies, trams, bowler hats, bicycles, and generally a quite pretty little city situated on the banks of a healthy Swan river full of prawns and crabs and fish. The ugly concrete high-rise buildings appeared in the 1950s and then really came into the streetscape in the 1960s and 1970s. Busy roads and freeways crisscrossed the Esplanade between the city and the river and you could no longer stroll down to the river’s edge after alighting from a tram. The old Perth went under.

Today in 2009 Perth is not a beautiful city in my eyes. However the land abides where it hasn’t been skinned by chronically industrious wajelas or white fellas. Even in the middle of the city, as Wendell Berry writes in his poem ‘In a Country Once Forested’, ‘under the pavement the soil is dreaming of grass’. Let me rephrase that: in Perth, under the pavement the soil is dreaming of grass trees.