Currently I’m interested in the evolutionary context of human movement and psychology. I believe that stress reduction in modern Western society can be achieved through moving for pleasure in wild natural environments for regular, if brief, periods. We are stone age children born to twentieth century mothers, and I believe that understanding our past can illuminate our present. For example Daniel Lieberman and others at Harvard University have studied the running biomechanics of barefoot populations and discovered that their forefoot style of running results in fewer running injuries. The advice that comes out of this research into how we used to get around as a species is that we should stop wearing shoes when possible, including when running on contemporary hard surfaces. I want to develop my own brand of ‘paleo-therapy’, an approach to physical therapy that encompasses an understanding of anatomy, evolutionary biomechanics, neuroscience, as well as eco-psychology, and regional environmental history. For now I’m going to leave you with a few images relevant to the path I’m exploring.

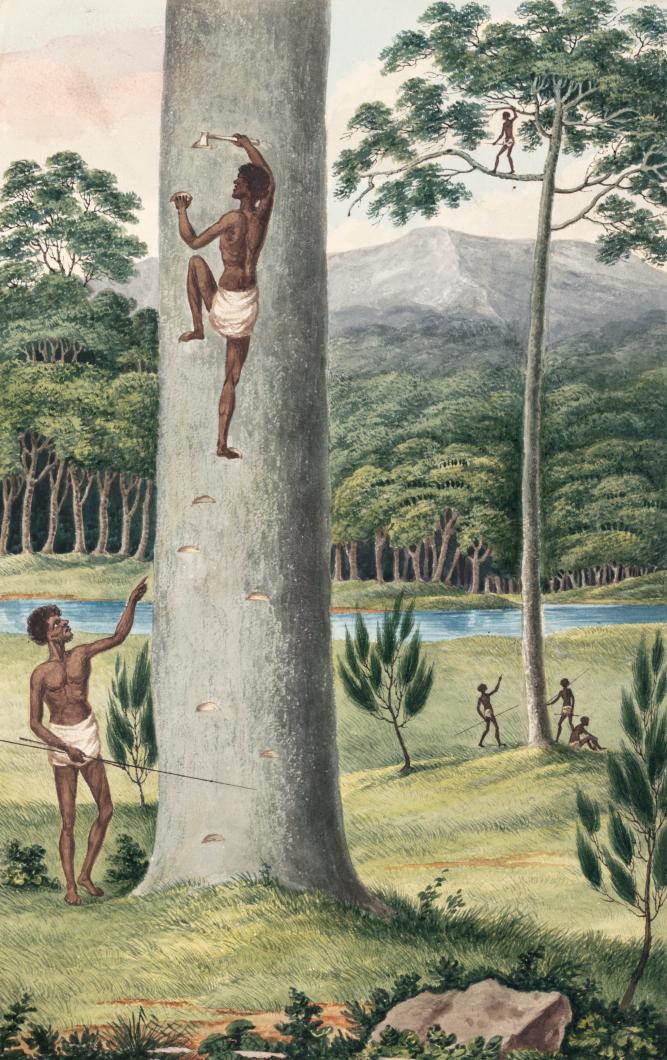

Early nineteenth century convict artist Joseph Lycett painted this canvas in eastern Australia, documenting an example of gatherer-hunters climbing (probably to harvest parrot eggs). Climbing is a fundamental human action.

Young children will climb spontaneously for the pleasure of the activity, even before they have achieved upright, bipedal locomotion. For most adults this activity is not practiced unless in the specialized context of ‘rock climbing’.

The next image comes from early nineteenth century Australian landscape painter John Glover, and shows the Australians dancing, evincing pleasure in non-functional human movement, celebrating movement in nature.

Today in the West human movement has largely been marginalized, and put into the frame of ‘exercise’, something which often takes the form of the industrial drudgery of the gym with its repetitive movements which build cosmetic fitness. Such ‘exercise’ does not enhance proprioception, facilitate pleasure through noncompetitive play, or enhance a connection with others or the natural world, as the activity in the above painting would have done.

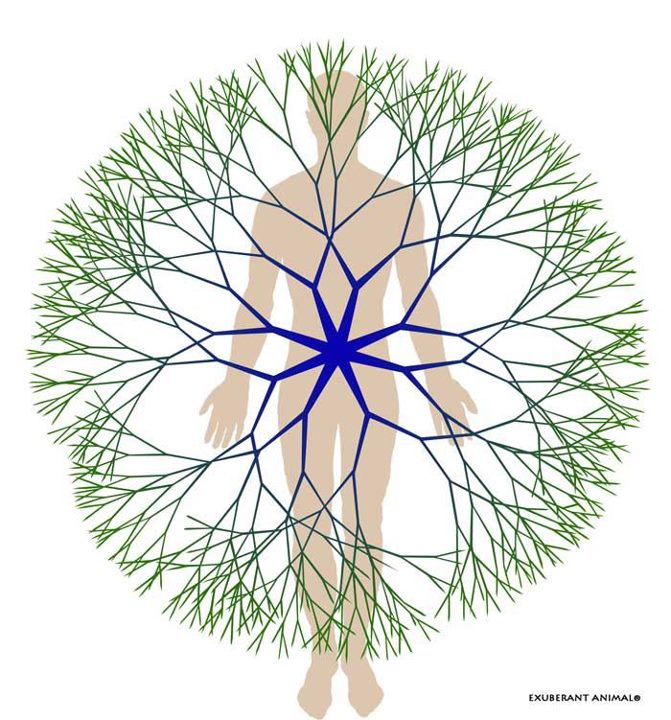

This image comes from Frank Forencich, author of The Exuberant Animal, and advocate of a return to human movement that takes its cues from our pre-agricultural ancestors. The form of representation combines the style of African cave paintings from a paleo environment with a sense of communion with non-human animals and a variety of playful human movements.

Many fundamental forms of human movement may have evolved in response to the challenges of hunting. Here photographer Charles Mountford documents an Australian hunter in 1940’s Northern Territory returning home after a hunt.

Joseph Lycett provides us with a pictorial representation of the hunt from early nineteenth century Australia. Lycett’s painting is deficient in that he represents the men wearing a form of loin cloth (for the sensibilities of his colonial British audience), where in reality they would have been closer to naked during the summer months.

Movement here is functional in that it ultimately provides large and concentrated protein intakes for the tribe, however the challenges of this activity require high levels of muscle strength, cardiopulmonary endurance, sensory-motor control, bioregional knowledge, vision, social cooperation, confidence and mental focus, and it may have even been fun now and again. The landscape is a human creation, the result of fine-grained patchwork burning practices which create a beautiful and useful Australian landscape. Human movement in relationship with others and with the natural world that is our home.

This image is again from Frank Forencich, and illustrates the importance of developing a sense of human identity nested in the natural world that is our home. We need to learn from the kinds and contexts of human movement of our human ancestors, gatherer-hunters who left north-east Africa around 70 thousand years ago and migrated around the world. A simple maxim of physiotherapy is ‘use it or lose it’, and many of us urban citizens need rehabilitation in fundamental human movement and a relationship with natural environments.

Practicing such movement is great for your mental health. As John Muir once wrote: ‘Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life.’

I will leave it at that for now… more to follow.