IN THE LATE nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Vienna was the best evidence that the most accommodating and fruitful ground for the life of the mind can be something more broad than a university campus. More broad, and in many ways more fun. In Vienna there were no exams to pass, learning was a voluntary passion, and wit was a form of currency. Reading about old Vienna now, you are taken back to a time that should come again: a time when education was a lifelong process. You didn’t complete your education and then start your career. Your education was your career, and it was never completed. For generations of writers, artists, musicians, journalists and mind-workers of every type, the Vienna café was a way of life. […] Most, though not all, of the café population was Jewish, which explains why the great age of the café as an informal campus abruptly terminated in March 1938, when the Anschluss wrote the finish—finis Austriae, as Freud put it—to an era (from Cultural Amnesia by Clive James, 2007).

Reading James’ words made me more sympathetic towards Vienna than I would otherwise have been. And for years I had known it was the city of Wittgenstein and Freud and Klimt and plenty of other intellectuals and artists. But that was years ago and this is now.

Having just made a brief visit to the city I found it a smallish and architecturally dignified city north of the Alps. Not a world capital.

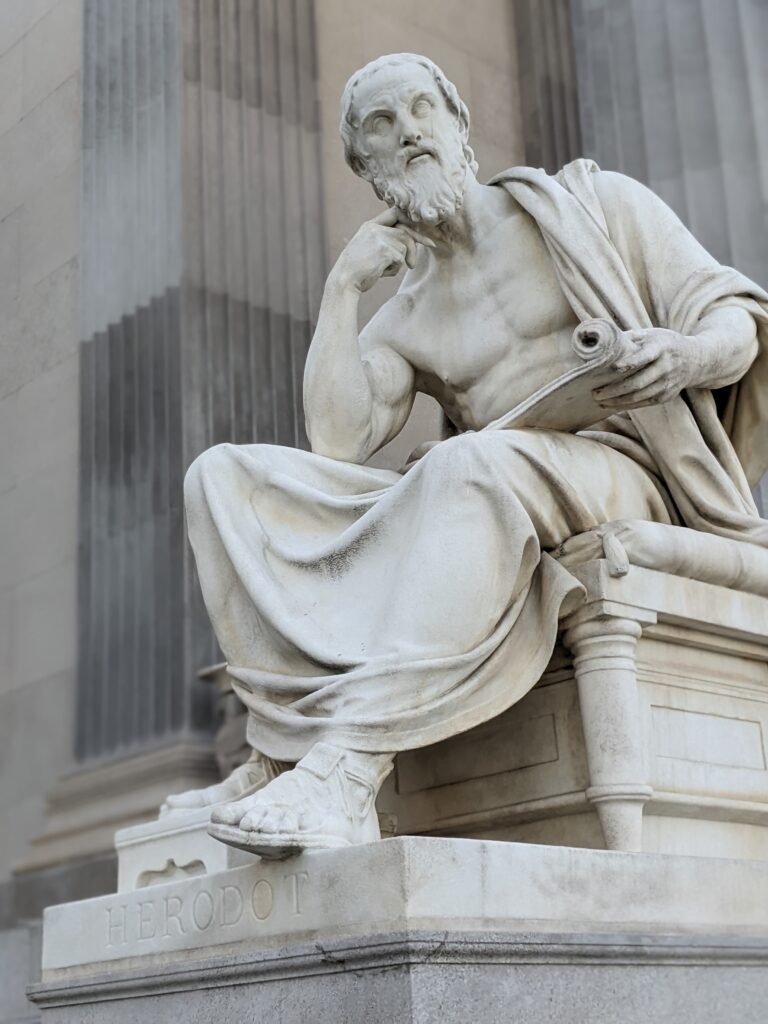

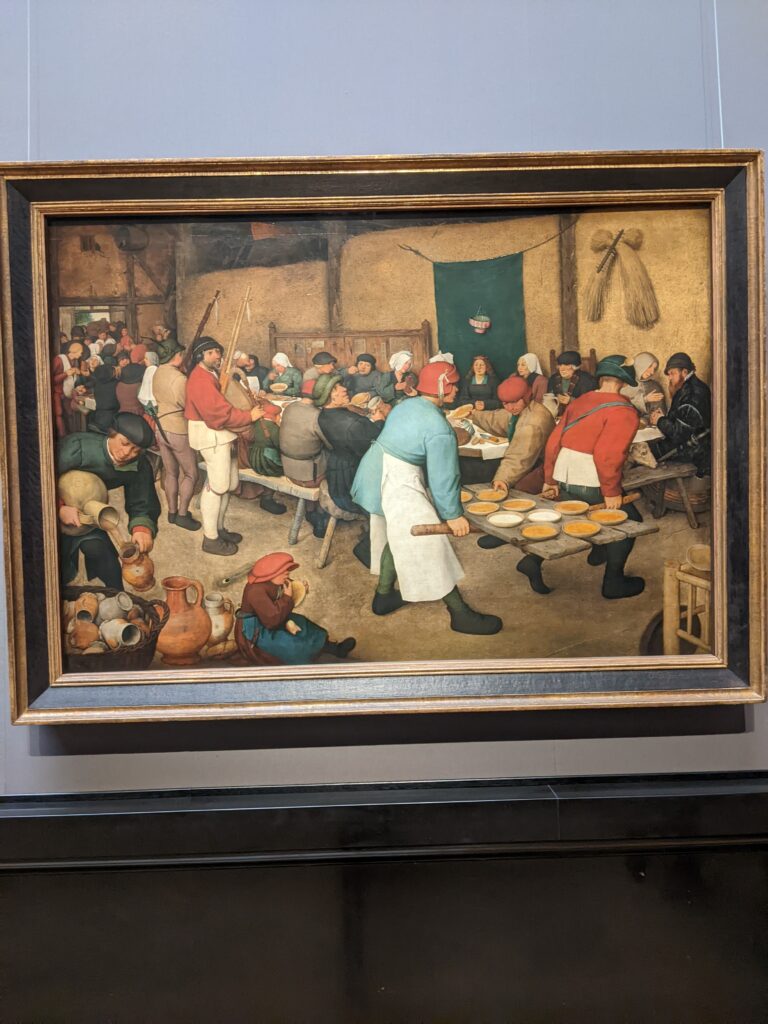

Yet it was. Vienna was the third largest city in Europe in the nineteenth century, after London (the biggest by far) and then Paris. Apparently Freud used to walk along the Ringstrasse to clear his head after a long evening’s writing. I walked there too, and enjoyed the tree lined boulevard lined with late nineteenth century neoclassical Parliament, neogothic Rathaus, and Renaissance Kunst history museum. On my first afternoon in Vienna I actually made it into the Kunst history museum with an old friend who moved here from Brazil several years ago. We walked to the room upstairs full of paintings by Brueghel. I stood in front of his Tower of Babel for a while. In this painting a huge tower is being built but it is falling apart in area – symbolising that the monoglot truth of humanity is crumbling into polyglot tribes. Perhaps this is a good symbol for the present state of the West as we become more stridently polarised on a political and cultural level. And I also stood in front of Brueghel’s The Peasant Wedding painting – the one I see when I visit two friends in Fremantle where a reproduction hangs on their wall. It is a good reminder of the humanity of people long ago in north-western Europe being individual personalities with individual stories and dramas played out in their own time, in the 1500s. In ways that still play out today, in different clothes, and with different material and technological environments, but otherwise with many of the same impulses and qualities stemming from a deeper human nature.

Vienna is a pretty city. Clean, full of caryatids on nineteenth century facades, and has very civilized koffee haus culture where you can find a table, get a newspaper and order your cup of coffee and slice of strudel and while away the afternoon. It has the ghost of the House of the Habsburgs lingering in it. You see this ghost atop the Hofburg in the shape of a two headed eagle in carved stone. The konig of Hungry looks one way, and the emperor of Austria looks the other, a two headed overlord. At the end of the line this overlord was a whiskered and side-burned Franz Joseph. The self-importance of this monarchs took a beating as in 1848 Europe was erupting with a rash of republican uprisings. And as the great buildings in stone went up on the Ringstrasse in Vienna the Austro-Hungarian Empire already had its days numbered. These buildings try to assert something that wouldn’t last.