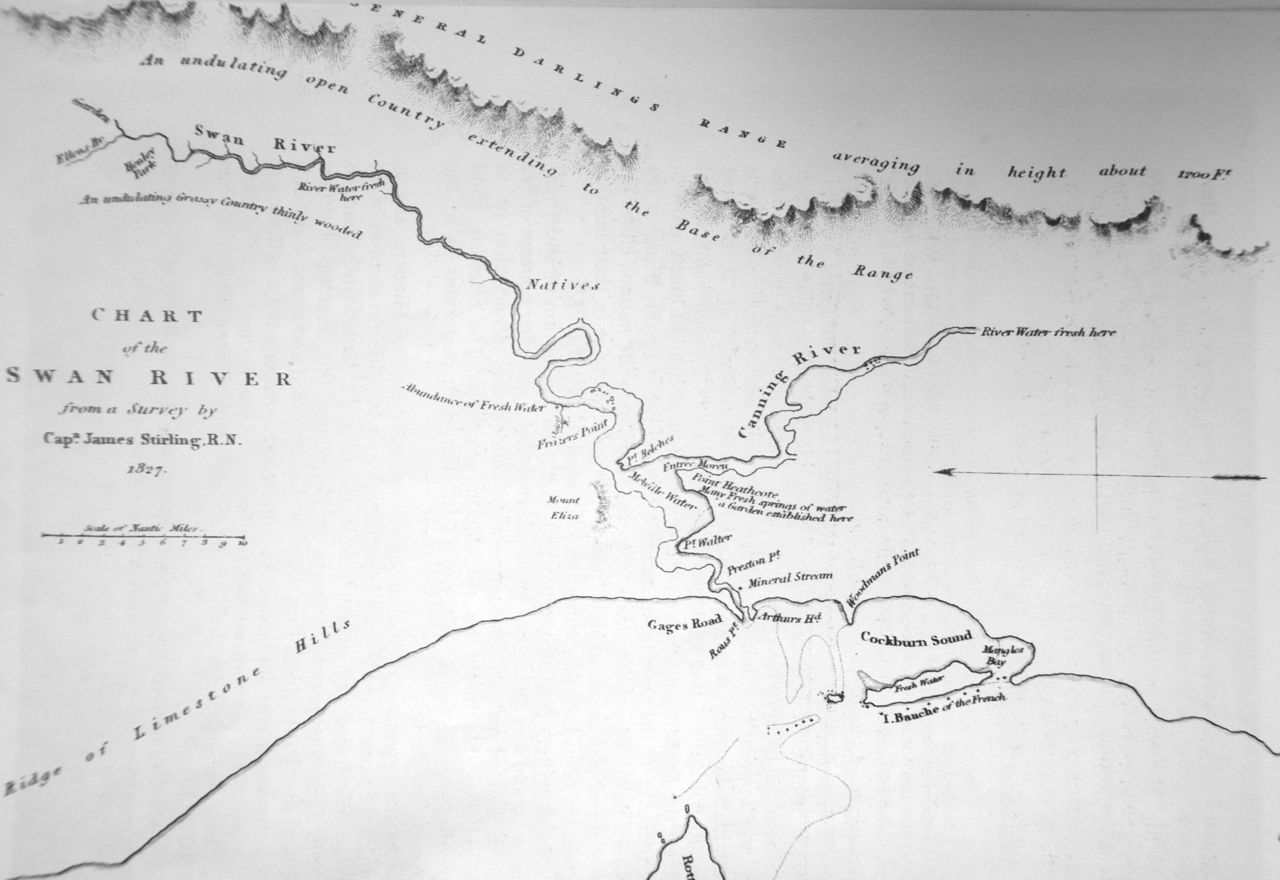

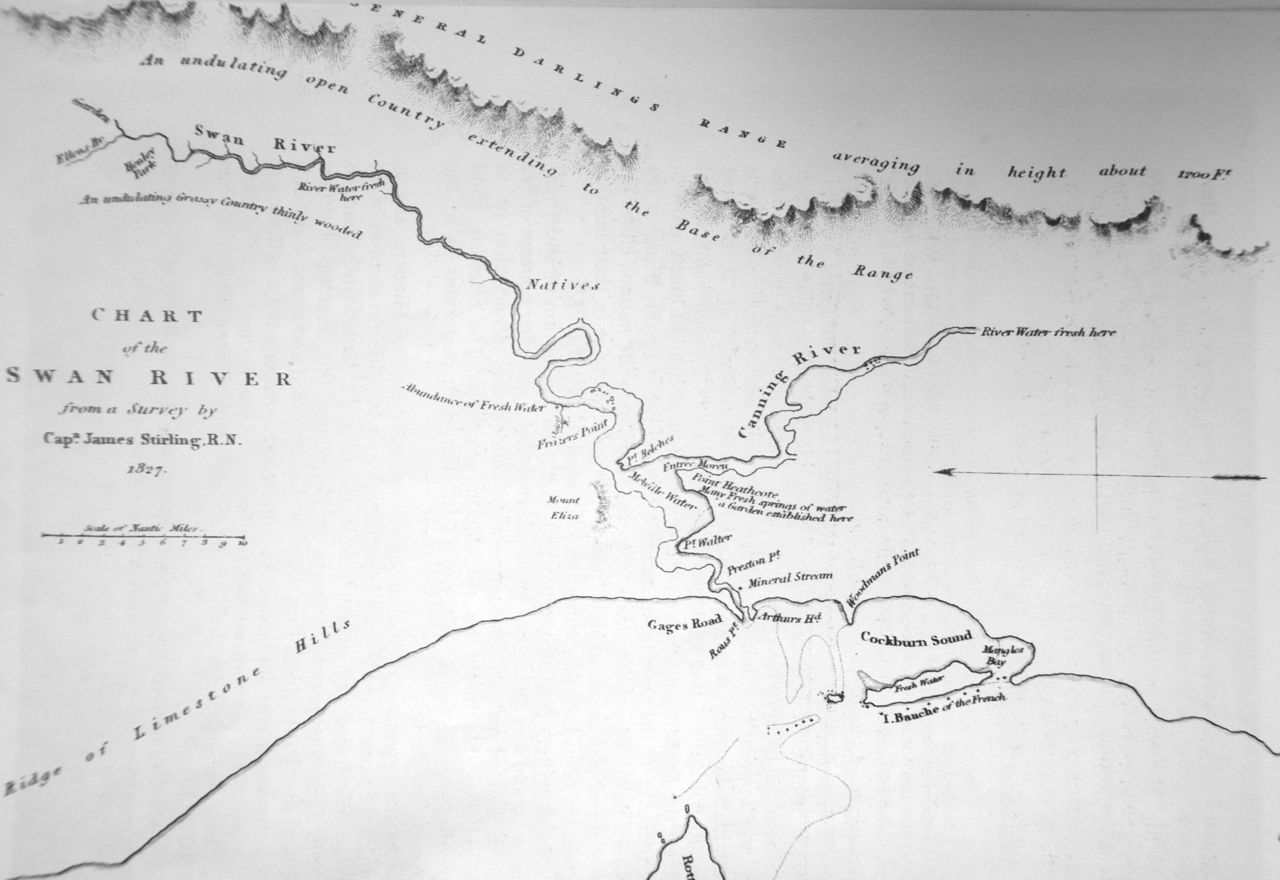

This is a map drawn by Captain James Stirling in 1827, when the captain was exploring the area prior to setting up the Swan River Settlement of British immigrants in 1829. Click on the above map and it will enlarge so you can read it better.

Kallip is an old Nyungar word meaning ‘a knowledge of localities; familiar acquaintance with a range of country… also used to express property in land’ (Moore 1884b:39, from Sylvia J. Hallam, Fire and Hearth: A Study of Aboriginal Usage and European Usurpation in South-Western Australia, Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1975, p.43).

Do you have kallip? Captain Stirling had more kallip than many contemporary citizens of Perth, but he didn’t have as much kallip as the Aboriginal people with their ecologically attuned awareness of seasons, animal behaviours and landforms. I try to have kallip. Where I live is not just a street name and number: I live on a sandy, limestone hill close to the Indian ocean, south and near the mouth of the Swan river. Stirling’s map is interesting to me as it captures many of the important aspects of the landscape, such as Mount Eliza, the prominence where today’s King’s Park stands, and most importantly, our river. Unlike most maps you will see today that depict the area on a north-south axis, this map makes the river a central point and a part of the landscape that streches out before, you, the viewer. The Swan is the centre. As it was for Aboriginal people here.

Come back to 1827. You are more likely to bump into people on the Swan coastal plain than, for example, in the thick karri forests to the far south. These people don’t live in tribes, but in what is more accurately described as large extended families of up to fifty people. Single men camp away from the married men, women and children. They are lean and walk with the ease of nomads. Some have headbands with Emu or Cockatoo feathers stuck in the side, rising regally above their faces. In winter they retreat to the area inland just below the Darling Range, away from the strong and chilly winds coming off the ocean. They hunt yonga, or kangaroos, at this time. The men leave the camp in the morning in groups of two or three and use the noise of the wind and the rain to provide cover as they stalk the yonga. They wear bukas, or long cloaks made of kangaroo fur fastened with a bone pin in front. Unlike out on uninhabited Rottnest island, the woodland here is full of huge, old djara, or jarrah trees, most with burn marks from past fires, and open green pasture underneath the trees. The lack of undergrowth here on much of the Swan coastal plain is due to the habit of the locals of seasonally starting small fires. It creates carpets of lush new growth the next year and good, green hunting pastures.

As the year progresses and summer approaches the people move westwards towards the coast and towards Fremantle. Beach time! More people get together. They step over soft, sandy ground. Banksia flowers start to glow yellow in the sun. The people collect them and steep them in little fresh water springs to taste a sweet liquid. Men climb trees by chipping foot holds in trunks with stone axes, and collect the eggs of parrots from holes in boughs far above the ground. Sometimes they visit the lakes south of Fremantle, like Manning Lake in today’s Hamilton Hill, and dig for frogs and tortoises, or yargan, in the mud at their edges. Women kill some norn, or snakes, to eat. They eat yams and other roots the women of the family dig up with their wonnas, or digging sticks. In the trunks of decaying balga, or grass trees, they find fat, white moth larvae to eat. As summer comes on fishing starts to become their main source of protein. The Swan river is alive and full of healthy shoals of big tailor, cobbler (Tandanus bostocki) and other fish. The locals fish by herding fish into the shallows and spearing them. Canoes and fishing hooks are not on the scene, but here and there weirs are used to trap fish.

Witness this land in 1827. A kwenda ambles along through the understory. A shy honey possums creeps through the leafy canopy above. You can hear the sound of Casuarina’s needles soughing in the wind. The day passes quietly, as it has for thousands of years. Come to the water’s edge. A tale is being told around a camp fire at the slow-flowing river’s shore. Behind the dark face of the narrator the western sky is lighting up another tapestry of coloured cumulus. A limb cracks and falls off an old Tuart tree further downstream. All eyes turn in the direction of the splash. The silence ripples outwards from the Tuart’s speech mark. Then the other story is resumed.

Later steaming fish are lifted from the ground and unwrapped from paperbark coverings. The aroma pervades the clearing and the humpies and brings appetite. Young people laugh and crack jokes.

The evening lengthens. As the light goes a huge flocks of black swans, hundreds and hundreds of them, suddenly take to the air. Although it is dark now the rush from the surface of the water is loud. They are taking off, just out of sight. Old eyes look out over the barely lit waters.

Old eyes can fail. Old eyes can flicker, and then close.

It is a deeper shade of black now. But in the centre the Swan keeps flowing, slow and sure. Not even forgetfullness can stop it.